A tea plantation worker sprays pesticides at Tata's Periakanal estate in Kerala, India. Photo: Vivek M. / Greenpeace

Revealed: The pesticide giants making billions on toxic and bee-harming chemicals

Groundbreaking joint investigation reveals enormous sales of ‘highly hazardous pesticides’ by leading members of the CropLife International lobby group

Revealed: The pesticide giants making billions on toxic and bee-harming chemicals

Groundbreaking joint investigation reveals enormous sales of ‘highly hazardous pesticides’ by leading members of the CropLife International lobby group

A tea plantation worker sprays pesticides at Tata's Periakanal estate in Kerala, India. Photo: Vivek M. / Greenpeace

The world’s five biggest pesticide manufacturers are making more than a third of their income from leading products selling chemicals that pose serious hazards to human health and the environment, a joint investigation by Unearthed and Public Eye has found.

Analysis of a huge database of 2018’s top-selling “crop protection products” has revealed the world’s leading agrochemical companies made more than 35% of their sales from pesticides classed as “highly hazardous” to people, animals or ecosystems.

The investigation identified billions of dollars of income for agrochemical giants BASF, Bayer, Corteva, FMC and Syngenta from chemicals found by regulatory authorities to pose health hazards like cancer or reproductive failure.

It also found more than a billion dollars of their sales came from chemicals – some now banned in European markets – that are highly toxic to bees. Over two thirds of these sales were made in low- and middle-income countries like Brazil and India.

By far the most valuable markets for the highly hazardous pesticides sold by these companies were the commodity crops soya and corn, grown in large part to provide animal feed for the meat industry.

Visualisations by Nadieh Bremer

Industry database

The database, obtained from leading agribusiness intelligence firm Phillips McDougall, covers $23.3bn in pesticide sales across 43 different countries. These sales represent the leading products in the world’s highest-spending pesticide markets, and amount to around 40% of the global agrochemical market.

Unearthed and Public Eye, an NGO that investigates human rights abuses by Swiss companies, combed this dataset for sales of chemicals on the Pesticide Action Network (PAN) International list of highly hazardous pesticides (HHPs).

The investigation found that close to half (41%) of the leading products of the agrochemical giants BASF, Bayer, Corteva, FMC and Syngenta contained at least one HHP.

There is a huge disconnect between what those companies are saying and what they are actually doing

Between them these companies control close to two thirds of the global agrochemicals market, and comprise five out of six members of the influential lobby group CropLife International.

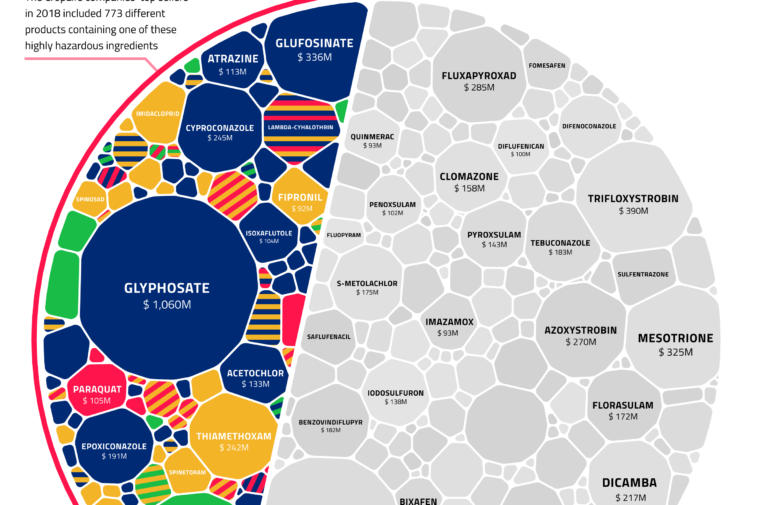

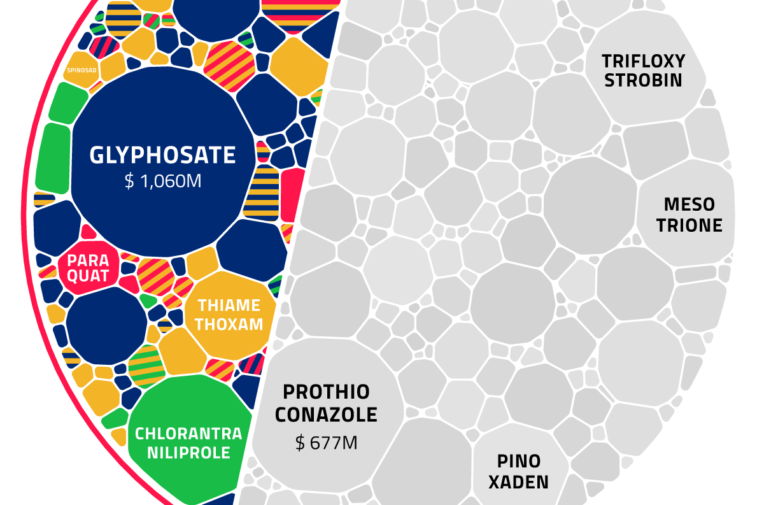

Of the $13.4bn of sales by the CropLife companies in the dataset, $4.8bn went on chemicals found by regulatory agencies to pose hazards like acute poisoning or chronic illness in people, or high toxicity to bees and other wildlife.

The group’s full annual income from these chemicals will be billions of dollars greater, because the data analysed covered less than half of total global sales.

The investigation’s key findings include that:

- The CropLife members made 10% of their leading products income ($1.3bn) from chemicals classed by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as highly toxic to bees. These include neonicotinoids produced by Germany’s Bayer and Switzerland-based Syngenta, which were permanently banned from outdoor use in the European Union in 2018. Brazil was their main market for these chemicals.

- CropLife members made almost $3bn (22% of sales) from chemicals found by regulators to pose chronic health hazards. Among their top sellers were BASF’s weedkiller glufosinate and Corteva’s fungicide cyproconazole, both classed by EU regulators as damaging to fertility, sexual function or the unborn child. But by far CropLife’s biggest seller was glyphosate, classed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a “probable human carcinogen”. Glyphosate manufacturer Bayer and various regulators have rejected this classification.

- CropLife members made $596m (4%) of sales from pesticides classed as highly toxic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) or as fatal if inhaled. Syngenta accounted for a large majority of these sales, with its top sellers including paraquat, a herbicide so toxic that a single sip can kill, which has long been banned in Europe and Switzerland.

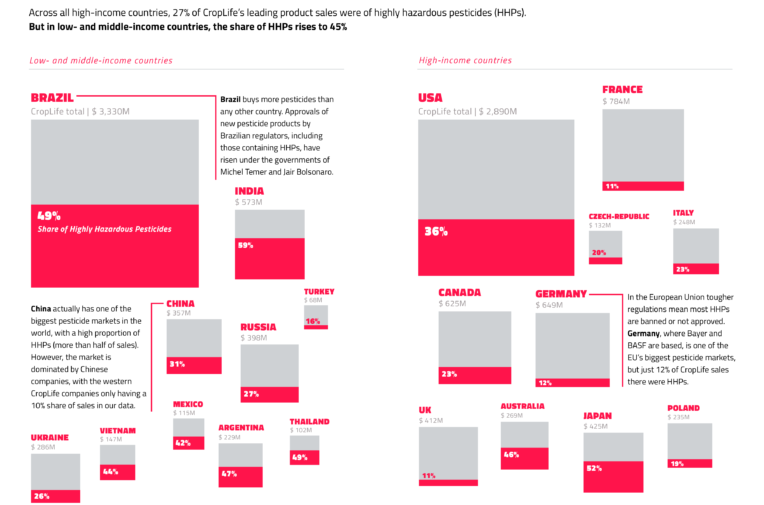

- The CropLife group made the majority of its highly hazardous pesticide sales in low- and middle-income countries like Brazil and India, where experts say the risks posed by using these chemicals are greatest.

- These companies’ biggest markets for highly hazardous pesticides were the commodity crops soya and corn. These two crops alone accounted for around half of CropLife HHP sales.

- These five companies alone accounted for almost half (48%) of all HHPs identified in the Phillips McDougall database.

Meriel Watts, a senior science and policy advisor to PAN, told Unearthed: “This investigation shows that there is a huge disconnect between what those companies are saying in the international policy arena and what they are actually doing.”

CropLife International is an influential trade association and lobby group for the world’s major agrochemical and agricultural biotech companies. Its members Syngenta, Bayer Crop Science, BASF, Corteva Agriscience, and FMC are the five biggest pesticide companies in the world by agrochemical turnover. CropLife’s sixth member is the Japanese company Sumitomo Chemical, the world’s 8th biggest pesticide company. Sumitomo is not included in this investigation.

In international negotiations on pesticide regulation, the CropLife International lobby group is a well-funded and influential voice. Its members include the five leading agrochemical companies by turnover, plus the Japanese company Sumitomo.

CropLife argues that HHPs are an “important tool to fight against crop losses” and should be used as a last resort to help farmers “produce enough food for a growing population”.

But the group says the majority of HHPs sold in developing countries are not manufactured by its members, and that its own members have “led by example” with measures like training millions of people in risk reduction techniques, such as wearing protective equipment.

However, Baskut Tuncak, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on toxic substances and human rights, rejected the idea that the risks posed by HHPs could be managed safely.

The impacts are unquestionable, but the system is rigged so that they are also unprovable

“There is nothing sustainable about the widespread use of highly hazardous pesticides for agriculture,” Tuncak told Unearthed. “Whether they poison workers, extinguish biodiversity, persist in the environment, or accumulate in a mother’s breast milk, these are unsustainable, cannot be used safely, and should have been phased out of use long ago.”

Unearthed and Public Eye’s investigation found that the CropLife companies made on average 27% of sales income from HHPs in high-income countries; but for low- and middle-income countries the proportion rose to 45%. In their most important LMIC markets, Brazil and India, HHPs made up 49% and 59% of sales respectively.

Tuncak commented: “We are in the midst of an invisible explosion of pesticide use in low-and middle-income countries that are ill-equipped to manage such hazards.

“Governments do not have enough capacity to monitor conditions on countless farms and plantations, analyse food and environmental samples, track the health of seasonal and migrant workers, investigate allegations of gross misconduct on farms and plantations, or verify the integrity of the information being provided by industry-funded scientists.

“From the testimonies of workers to the collapse of biodiversity, the impacts are unquestionable, but the system is rigged so that they are also unprovable.”

CropLife itself says that its members reviewed their entire portfolios between 2015 and 2016 and concluded that only 15% of their products were HHPs.

Further, they found that 10% were HHPs “that can be used safely and responsibly” and only 2.5% “required risk mitigation measures or were withdrawn from the market”.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN (FAO) define HHPs as “pesticides that are acknowledged to present particularly high levels of acute or chronic hazards to health or the environment according to internationally accepted classification systems”. Environmental hazards include problems like water source contamination, or “disruption of ecosystem functions” like pollination. However, they have never produced a list of HHPs. To fill this gap Pesticide Action Network International produces the only consolidated list, which is based on classifications made by the WHO, the European Chemicals Agency, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, and the US EPA.

CropLife International declined to tell Unearthed which of its members’ products it classed as HHPs. However, its director of international regulatory affairs Christoph Neumann said their analysis had probably differed because they used different criteria to the Pesticide Action Network for defining HHPS.

In particular the group objects to the use of what it calls “environmental” criteria by PAN.

“The criteria cited by PAN are often environmental criteria that are not agreed or yet endorsed” by the FAO and the WHO, he explained.

Driven toward extinction

The only detailed classifications the UN agencies have so far agreed for HHPs concern effects on human health, like acute poisoning or cancer.

This has led pesticide companies to argue that there are in effect no globally agreed standards for classing a pesticide as highly hazardous on environmental grounds.

This argument may not last. A 2019 publication by the FAO and the WHO suggests there are strong grounds for classing neonicotinoid insecticides as highly hazardous.

We are losing wildlife, particularly insects. The crisis is driven by a combination of factors but there is no doubt that pesticides are harming pollinators

There is, it states, a “rapidly growing body of evidence” that “existing levels of environmental contamination” by neonicotinoids “are causing large-scale adverse effects on bees and other beneficial insects”.

“The need to severely restrict their use and prevent future registration is gaining a large consensus,” it continues. “The European Union has already issued a complete and permanent ban on all outdoor uses of the three most commonly used neonicotinoid pesticides: clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam.”

Three quarters of the world’s food crops depend at least in part on pollinators, and a growing number of pollinator species worldwide are being “driven towards extinction”, according to a global 2016 study.

UN special rapporteur Baskut Tuncak told Unearthed that the threat neonicotinoid pesticides “present to our food security and our biodiversity is a human rights concern, in and of itself”.

The neonicotinoid thiamethoxam was Syngenta’s biggest selling HHP in 2018, our investigation found, accounting for 7% of the company’s sales ($242.5m). Similarly, imidacloprid was in Bayer’s top ten biggest selling HHPs, with sales of $101m. In both cases, the main market was Brazil – a country that hosts up to 20% of the world’s remaining biodiversity.

In addition to these neonicotinoids, Unearthed and Public Eye identified a further 37 chemicals sold by the CropLife companies that are classed as highly toxic to bees.

Among them were chlorfenapyr and fipronil – another chemical linked to mass bee deaths – manufactured by the German chemicals giant BASF.

Syngenta and BASF both declined to comment directly for this story. Syngenta – which was responsible for close to half (42%) of CropLife’s $1.3bn of bee-toxic pesticide sales – has recently argued that journalists are “overstating the science that clearly exists” on insect declines.

However, University of Sussex biology professor Dave Goulson told Unearthed: “There is overwhelming evidence that we are in the middle of a biodiversity crisis, with extinction roughly 1,000 times the natural rate.

“We are losing wildlife, particularly insects. The crisis is driven by a combination of factors but there is no doubt that pesticides are harming pollinators.”

The toxic top 10

The most common category of hazard in the CropLife members’ top sellers is chronic health effects like cancer, birth defects, or endocrine disruption.

Chemicals classed as posing these hazards accounted for $3bn (22%) of the CropLife sales we analysed, and seven of the group’s top ten HHPs.

It is absolutely clear that glyphosate can cause cancers in experimental animals

By far the biggest of these was glyphosate, the world’s most popular weedkiller, which accounted for $1.1bn of CropLife sales. Bayer alone accounted for $840m of those sales, as a result of its controversial 2018 takeover of Roundup manufacturer Monsanto.

A spokesman for Bayer Crop Science told Unearthed it was “incorrect” to class the herbicide as highly hazardous simply on the strength of its IARC classification as a “probable human carcinogen”.

He added that “leading health regulators around the world” – including the USEPA and the European Food Safety Authority – had “repeatedly concluded that our glyphosate-based products can be used safely as directed and that glyphosate is not carcinogenic”.

Glyphosate is currently authorised in the EU until 2022, but various countries including Germany have announced their intention to ban it by 2023 even if the EU extends its licence.

Chris Portier, a former director of the US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry who worked on the IARC’s review of glyphosate, said he believed the agency’s classification was “exactly right”. “It is absolutely clear that glyphosate can cause cancers in experimental animals,” he told Unearthed.

“And the human evidence for an association between glyphosate and cancer is also there, predominantly for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.”

In the US, which is Bayer’s biggest glyphosate market according to our investigation, the company is facing lawsuits from tens of thousands of plaintiffs who allege Roundup gave them cancer. Fortune magazine recently reported that the company may anticipate spending $10bn to resolve current and future claims.

The CropLife members’ highly hazardous top ten also includes $336m sales of the herbicide glufosinate, $245m of the fungicide cyproconazole, and $191m of the fungicide epoxiconazole, all of which are classed as “reproductive toxicants” in the EU, believed capable of damaging fertility, sexual function, or the unborn child.

Many HHPs have now been phased out in the EU, which has some of the toughest pesticide regulations in the world. That, however, is not the case for BASF’s epoxiconazole, which includes Germany and the UK among its four most important markets, the investigation found.

Elsewhere, the CropLife HHP top ten includes a clutch of chemicals manufactured and sold by European companies that have long been banned in their home markets.

Among these are the herbicides paraquat and atrazine, both sold by several CropLife companies but mainly Syngenta. Both of these chemicals have been around since the 1960s, and are now banned in the EU and Switzerland.

Accidental or deliberate ingestion of even a small amount of paraquat is frequently fatal, and it is a leading means of suicide in poor and rural areas where it remains available.

Atrazine was banned in Europe over concerns about groundwater contamination, but it is also classed by the EU as an endocrine disruptor, and researchers in the US have found it “wreaks havoc with the sex lives of male frogs”.

Get stories like this in your inbox every week

Sign up to receive weekly and breaking news stories from Unearthed, plus very occasional emails with petitions, campaigns, fundraising or volunteering opportunities from Unearthed or Greenpeace

We promise that we’ll never sell or swap your details and you can opt out at any time – check our privacy policy.

The top ten also shows Bayer selling $125m of acetochlor, a weedkiller that was banned in the EU over concerns about contamination of drinking water and genotoxicity. The EU ban also cited a “high acute risk” to birds from contaminated drinking water.

Unearthed submitted detailed questions to all the companies mentioned in this article, but all except Bayer allowed Croplife to respond on their behalf.

A spokesman for Bayer Crop Science said the company did not agree with the classification of Bayer products as HHPs, because these products were neither classified as highly toxic to humans by the WHO, nor listed for control under the Stockholm Convention, the Rotterdam Convention, or the Montreal Protocol.

This amounts to just four of the eight categories of HHPs that have already been agreed by the FAO and the WHO. But the Bayer spokesman said that for the other categories – including pesticides proven or presumed to be mutagens, reproductive toxicants, or carcinogens – there was “currently no internationally responsible body for classification”.

He added that it was “not correct” that the Phillips McDougall data treated all Monsanto sales from 1 January 2018 as Bayer sales, when the takeover was completed on 7 June 2018.

After this story was published on 20 February 2020, Bayer published a statement expanding on why it disagreed with the classifications used by PAN. The statement added that Bayer was in the process of withdrawing products containing the pesticides methiocarb and carbendazim. Methiocarb is classed as acutely toxic by the WHO, while carbendazim is classed by the ECHA as presumed mutagen and reproductive toxicant.

CropLife International’s director of international regulatory affairs Christoph Neumann added that of the 19 chemicals our investigation identified as its members biggest selling HHPs, 12 were registered for use in the EU and 18 were registered for use in the US.

He continued: “CropLife International members support the International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management and agree with the principle of pesticide risk reduction. We support countries to identify, and if necessary, remove HHPs from their markets.”

He added: “When risk mitigation measures or good marketing practices are insufficient to ensure that the product can be handled without unacceptable risks to humans and the environment, then market withdrawal should be considered.”

This investigation is based on analysis of a huge dataset of pesticide sales from the agribusiness intelligence company Phillips McDougall. This company conducts detailed market research all over the world and sells databases and intelligence to pesticide companies. The data covers around 40% of the $57.6bn global market for agricultural pesticides in 2018. It covers 43 countries, which between them represent more than 90% of the global pesticide market by value. And it focuses on sales of leading products in the most valuable “market segments” (an example of a market segment would be insecticides for cotton in India).

We used the same methodology that pesticide industry analysts use to break up the value of product sales by active ingredient (in cases where a product included more than one active chemical), and we then established which of these chemicals had been classified by recognised authorities as posing environmental hazards like toxicity to bees, or hazards to humans, like acute toxicity, or chronic exposure risks like cancer.

For the final stage we used the 2019 highly hazardous pesticides list created by Pesticide Action Network International, which collates all pesticides that have been ascribed one of these hazard categories by the World Health Organisation, the European Chemicals Agency, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, or the US Environmental Protection Agency.

In June 2018 the agrochemicals company Monsanto was taken over by Bayer. The Phillips McDougall data treats all Monsanto sales in the early part of 2018 as Bayer sales.

Any reference to the group of CropLife companies or CropLife members in this article refers only to BASF, Bayer Crop Science, Corteva Agriscience, FMC, and Syngenta.

Visualisations by Nadieh Bremer / Visual Cinnamon

Update: This story was updated at 1.35pm on 20 Feb 2020, to add details of Bayer’s supplementary statement.