An aerial view of the Pantanal in Brazil. The wetlands flood seasonally, in the rainy season. Photo: Markus Mauthe / Greenpeace

Fires in Brazil’s Pantanal wetland and Amazon rainforest worst in a decade

A historic drought and increased land clearing are providing ideal conditions for fires to burn out of control in both biomes, while some researchers see climatic links between Amazonian deforestation and Pantanal fires

Fires in Brazil’s Pantanal wetland and Amazon rainforest worst in a decade

A historic drought and increased land clearing are providing ideal conditions for fires to burn out of control in both biomes, while some researchers see climatic links between Amazonian deforestation and Pantanal fires

An aerial view of the Pantanal in Brazil. The wetlands flood seasonally, in the rainy season. Photo: Markus Mauthe / Greenpeace

Brazil is ablaze. More fires are tearing through the Pantanal, the world’s biggest wetland, than during any other year since records began in 1998. And in the Amazon, fires in August were even worse than last year, when the world looked on in horror at images of smoke-blackened skies.

Amazon fire data from Brazil’s space agency INPE currently show a slight dip in August from last year due to a faulty Nasa satellite. But Alberto Setzer, the scientist in charge of fire data, told Reuters and confirmed to Unearthed that once this data was amended, he expected August to show an increase compared to last year of between 1% and 2%, making it the worst monthly result for a decade with an expected total of about 31,500 fires.

As the Amazon burns, a similar tragedy is unfolding in its neighbouring marshlands: Scant rain, accelerating deforestation and hamstrung environmental oversight are creating the ideal conditions for fires to proliferate.

Brazil’s Pantanal, a Unesco heritage site, extends some 150,000 sq km through central-western Brazil and across the border into Bolivia and Paraguay. Known for the variety and density of its wildlife, it floods seasonally and is home to hundreds of bird species, including the rare hyacinth macaw, and large endangered mammals like jaguars, maned wolves and giant anteaters.

According to the Instituto Centro de Vida (ICV), a forestry NGO based in Mato Grosso, at least 17,000 sq kms of Pantanal vegetation in Mato Grosso state have already been burned this year, an area about eleven times larger than London.

INPE registered a 220% jump in fires so far this year in the Pantanal, to a total of 10,153 hotspots, accelerating through July and August as the dry season progresses. More than half of this year’s fires were registered in August, which saw four times as many fire spots, 5,935, as the average for that month. The monthly total is significantly higher than any other year except 2005, when 5,993 fires were registered.

What 2005 and 2020 have in common is devastating drought; The Paraguay river is at its lowest level in almost half a century.

“We are suffering the biggest and longest drought in the last 47 years, which makes river levels extremely low and makes vegetation more vulnerable to fire,” said Professor Letícia Couto Garcia, an ecologist from the Federal University of Mato Grosso. “The deficit in rainfall has allowed dry plant biomass to accumulate, increasing the fuel load for fires.”

What makes fires in the Pantanal particularly difficult to control, said Professor Mercedes Bustamante, an ecologist from the University of Brasília, is that the seasonal flooding of the marshy land makes the soil itself carbon-rich and flammable.

“The soil is rich with organic material which allows fires to actually burn underground, through the area, like peat,” Bustamante said. “So you might think it is controlled but then it comes up from the fire in the soil, and starts burning overground again.”

But drought isn’t the only thing driving increased fires in the Pantanal. Deforestation in the biome, while not on the same scale as in the Amazon, is accelerating, and fires are often set to burn up felled trees and vegetation on recently deforested land.

Garcia said that illegal deforestation in the biome had more than doubled in the first six months of this year, to 133 sq kms from 64 sq kms during the same period last year. This increase is likely to be driven by expanding agriculture – according to Mapbiomas, an organisation which tracks land use change, the area devoted to pasture in the Pantanal increased by 210% from 1988 to 2018, from 8,600 sq km to 26,700 sq kms.

“Budget cuts, reducing emergency resources for those responsible for fire management, resources for training more firefighters, resources for equipment and vehicles for combat, and impunity for the causes of fire … [are also] factors that aggravate the situation,” said Garcia.

Critics say that in the Amazon and in the Pantanal, land-grabbers and ranchers have interpreted President Jair Bolsonaro’s vocal contempt for conservation as carte blanche to clear more land, and that environmental agencies, held back by budget cuts and a pandemic, have little recourse to stop them.

Just last week, Brazil’s Environment Ministry said it would halt all its efforts to stop deforestation in the Amazon, citing lack of funds, before dramatically reversing the decision hours later.

Vinicius Silgueiro, a forest engineer at ICV, said that it was clear as early as the end of 2019, from low rainfall and rainy season flood levels, that the Pantanal would be exceptionally vulnerable to fire this year. It ought to have been possible to plan more effectively for the disaster, he added, but the current administration lacked the political will to do so.

Silgueiro added that the tools existed to bring to justice those responsible for environmental destruction, but they were simply not being used.

“ICV studies show that in recent years, more than half of all the deforestation and fires in Mato Grosso states occur on properties registered with the CAR,” Silgueiro said, referring to the rural property registry. “This means that the federal and state governments have all the data on the owners of these areas, and accountability is possible.”

The coronavirus pandemic has also aggravated the situation, said Garcia, as indigenous firefighters – who make up a third of the Mato Grosso do Sul fire brigade – had to isolate within their territories.

Connected ecosystems

What this year’s fires show, experts say, is that the degradation of Brazil’s biomes, each ecologically crucial, is closely interconnected in a way that makes trying to protect one biome at the expense of another futile.

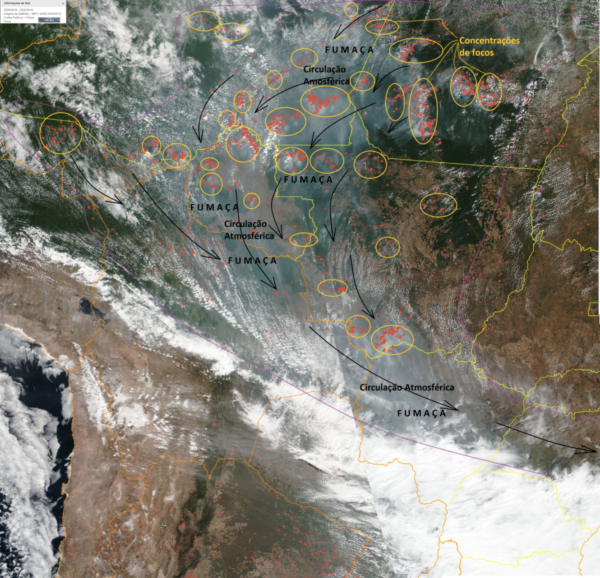

Most of the moisture that feeds the Pantanal by air comes from the Amazon, in the form of air masses loaded with water vapour taken up from the humid rainforest. These “flying rivers”, as they are known, travel across the country and are released as heavy rains over the Pantanal and the Cerrado, as well as parts of Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay. As the Amazon is cut down and fragmented, less evapotranspiration of moisture is available, and rainfall over the rest of the continent decreases.

Some researchers have also suggested a climatic link between unusually warm Atlantic ocean temperatures, intense Atlantic hurricane seasons – like this year – and bad years for Amazonian drought and fires, said Ane Alencar, director of science at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM). Alencar added that it was reasonable to posit a further link with Pantanal fires, as an Amazonian drought year will mean less moisture available for the flying rivers which flood the wetlands.

“If we take a look at the numbers of fire indications since 1998 when monitoring began, the only year where the Pantanal had such a very strong peak in the number of fires was 2005,” Alencar said. “And 2005 was one of the worst hurricane seasons, with Katrina and others, and we had a very strong drought in the western and southwestern Amazon.”

Meanwhile, the Pantanal’s most important waterway, the Paraguay River, is fed from headwaters in the vast central highlands of the Cerrado, a biodiverse biome of savannah and gallery forest spreading south and east of the Amazon and the Pantanal.

The Cerrado also relies heavily on “flying rivers” from the Amazon, and is crucial for Brazil’s water supply: it feeds six of the country’s eight river basins, and Brazil’s major aquifers. But it’s also desperately threatened, and has already lost some 50% of its native vegetation, mostly to vast monoculture farms producing commodity crops like soy.

This is also likely to be altering climatic patterns: the clay soil of the Cerrado acts like a sponge, and its native plants grow deep roots that store moisture and drain rainwater slowly back underground. Shallow-rooted soy crops are unable to replenish the aquifers deep underground, contributing to longer dry seasons and more frequent and intense droughts.

Some critics say that the global effort to protect the Amazon has simply displaced Brazil’s agricultural expansion to the Cerrado. It doesn’t appear to be slowing down: one recent study predicted Brazil’s soy acreage would expand by a further 124,000 sq kms by 2050, with most of this, 108,000 sq kms, concentrated in the Cerrado.

“These [ecological] processes don’t know about political borders and biome borders,” Bustamante said. “If you think, ok, I will protect the Amazon but I will expand agriculture in the Cerrado, this will have impacts in the Pantanal and the semi-arid Caatinga biome as well.”

“If you don’t have an environmental policy that looks at the whole country it will fail,” she added.

Unfortunately, Bustamante said, the opportunities for even the most basic scientific dialogue with the current administration had winnowed to practically zero.

“I’ve dealt with other governments and they weren’t perfect, but we were invited. We could give opinions and criticisms,” Bustamante said. “But now? They just deny what is going on. It is very hard to fight that attitude with facts.”