Weedkiller is sprayed on a soybean field in the Cerrado plains near Campo Verde, Mato Grosso state. Brazil is one of the top destinations for the EU’s banned pesticide exports. Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba / AFP / Getty

Thousands of tonnes of banned pesticides shipped to poorer countries from British and European factories

Year long investigation reveals full scale of Europe’s ‘abhorrent’ trade in pesticides banned from its own farms - and the UK’s leading role

Thousands of tonnes of banned pesticides shipped to poorer countries from British and European factories

Year long investigation reveals full scale of Europe’s ‘abhorrent’ trade in pesticides banned from its own farms - and the UK’s leading role

Weedkiller is sprayed on a soybean field in the Cerrado plains near Campo Verde, Mato Grosso state. Brazil is one of the top destinations for the EU’s banned pesticide exports. Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba / AFP / Getty

The United Kingdom is by far Europe’s biggest exporter of toxic banned pesticides to poorer countries, an Unearthed and Public Eye investigation has revealed.

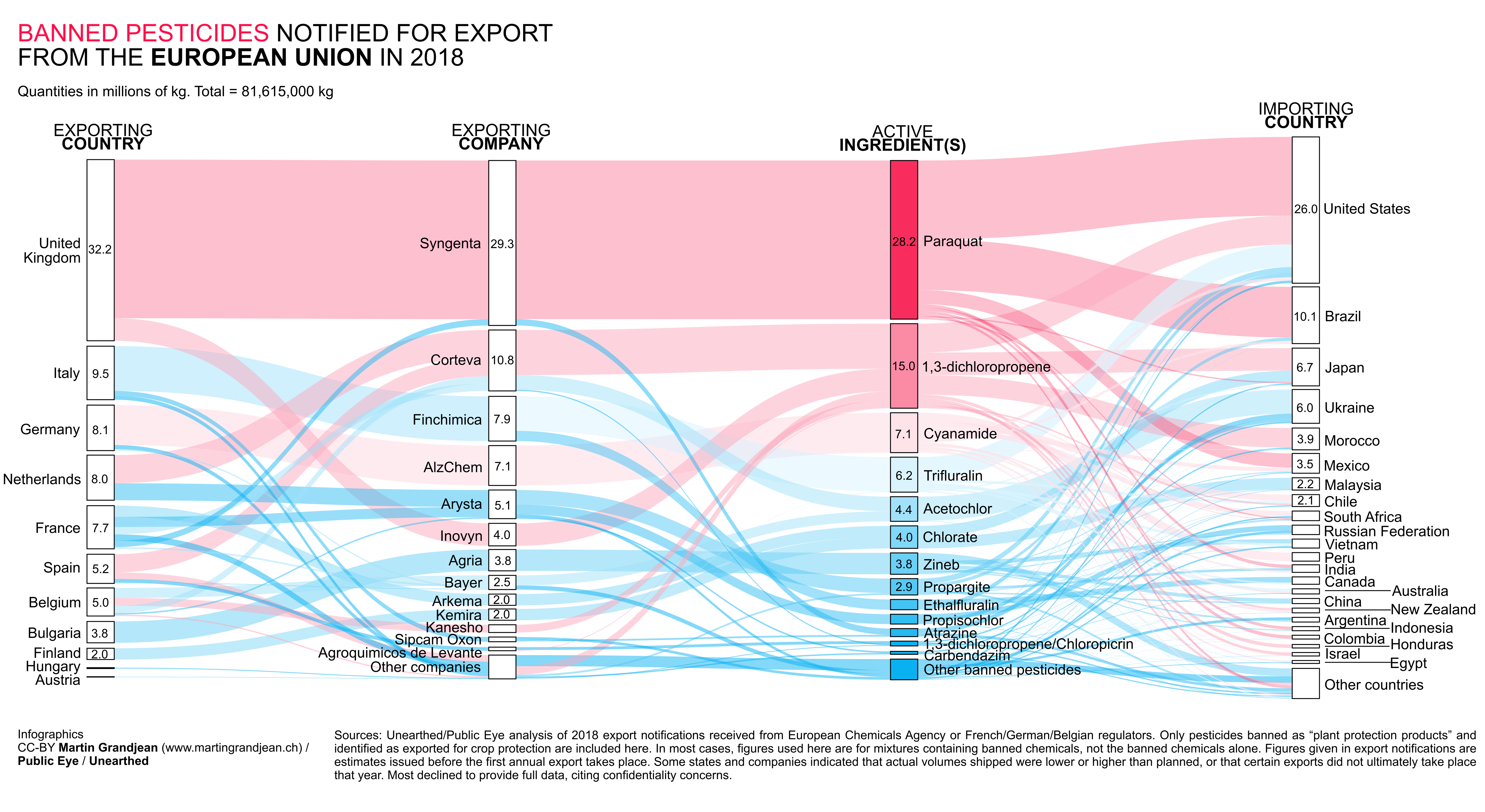

It found that EU countries issued plans in 2018 to export more than 81,000 tonnes of pesticides containing chemicals prohibited in their own fields.

Poorer countries like South Africa, Ukraine, and Brazil – where experts warn hazardous pesticide use poses the greatest risks – were the intended destination for the bulk of shipments.

The UK was responsible for 13,760 tonnes of those planned shipments to low- and middle-income countries – close to three times the amount attributable to any other exporter.

Among the banned agrochemicals shipped by the tonne from EU ports were substances found by the EU’s own authorities to pose potential health hazards like reproductive failure, endocrine disruption or cancer, and environmental hazards like groundwater contamination or poisoning of fish, birds, mammals or bees.

Loopholes in European law mean chemical companies like Bayer and Syngenta can continue making pesticides for export long after they have been banned from use in the EU to protect the environment or the health of its citizens.

Visualisations by Martin Grandjean

The full data is available here.

The companies and states that shipped these products told Unearthed that different parts of the world had different climates which needed different pesticides, and every nation had the sovereign right to decide which chemicals its farmers could use.

But campaigners in the importing nations said this was a “double standard” which placed a lower value on lives and ecosystems in poorer countries.

“If a pesticide is banned for causing cancer in the EU it will cause the same problems in Brazilian people,” said Alan Tygel, spokesperson for the Permanent Campaign Against Pesticides and for Life, a Brazilian umbrella group of social movements and NGOs. “The climate and agriculture are different, but the human bodies are very much the same.”

Unearthed and Public Eye, an NGO that investigates human rights abuses by Swiss companies, filed multiple freedom of information requests to regulators across the EU for the paperwork companies must produce if they want to export banned chemicals.

The investigation netted hundreds of documents revealing 11 different EU member states involved in the export of banned ‘crop protection products’.

But by far the biggest exporter by volume was the UK, the origin of 32,188 tonnes of planned exports – almost 40% of the total.

The vast bulk of the UK’s notified exports – 28,185 tonnes – were mixtures containing paraquat, a long-banned weedkiller manufactured in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, by the agrochemical giant Syngenta. It is so toxic that a sip can kill, making it a common cause of fatal suicide attempts in poorer countries, and has been found by scientists to increase risk of Parkinson’s disease.

The investigation’s findings come after three dozen United Nations human rights experts issued a statement this summer calling on wealthy nations to end the “deplorable” practice of exporting banned pesticides to poorer countries with weaker regulations.

In response to Unearthed and Public Eye’s investigation, Baskut Tuncak, the then-UN special rapporteur on toxics who drafted this summer’s statement, said he was “honestly shocked and appalled” to learn of the amount of paraquat being exported from the UK. This was, he said, an “unquestionably hazardous pesticide that is killing countless people around the world and resulting in who knows how many cases of health impacts such as Parkinson’s”.

Syngenta denies that existing science shows a causal link between paraquat and Parkinson’s disease.

In the July statement, Tuncak described the export of banned chemicals to poorer countries as a form of “exploitation” that shifted the health and environmental consequences of these products onto “the most vulnerable,” particularly “communities of African descent and other people of colour”.

The “loopholes” that allowed this cross-border trade were “a political concession to industry, allowing their chemical manufacturers to profit from inevitably poisoned workers and communities abroad, all the while importing cheaper products through global supply chains and fuelling unsustainable consumption and production patterns”.

In 2022, France will become the first EU country to impose a ban on the export of banned pesticides, after a legal challenge by agrochemical companies was defeated earlier this year. But Tuncak told Unearthed there needed to be an EU-wide ban.

“The European Union as a whole needs to demonstrate leadership to other countries around the world on this issue,” he said. “From there I think we can move towards an even broader consensus on ending this abhorrent practice of discrimination and exploitation.”

Unearthed and Public Eye’s investigation found a close correlation between Europe’s preferred sources of food imports and its banned pesticide sales. The countries that are the EU’s most important sources of agricultural produce – the United States, Brazil, and Ukraine – were all among the top five destinations for the EU’s banned pesticide exports.

The paper trail

The practice by manufacturers of continuing to export chemicals from the EU after they have been banned domestically is not new, but the key players have always been obscured by a veil of commercial confidentiality.

One of the few restrictions placed on these exporters is the Rotterdam Convention on international trade in hazardous pesticides and chemicals. This UN convention requires countries to share information about the dangers of their banned chemical exports with the importing countries.

Apparently the earnings of shareholders are more important than people’s health and the environment in the vast tracts of land that are exploited to produce raw materials for the EU market

The idea is to give poor countries that do not have resources to do their own research the opportunity to make an informed decision on whether to accept the exports.

Under EU rules, any company that wants to export banned chemicals needs to produce an “export notification” detailing the reasons the product is banned, its intended uses, and the amount the company intends to ship. National and EU regulators check these documents and issue them to authorities in the destination countries.

These notifications are not a perfect record – quantities actually exported may end up being greater or less than estimated, and some notified exports do not take place in a given year – but they are the most precise paper trail available for the EU’s trade in banned agrochemicals.

To cut through the secrecy of this trade, Unearthed and Public Eye spent months filing requests for these documents to the European Chemicals Agency, and regulators in Germany, France, Belgium and the UK. This produced the most complete record of banned agricultural pesticides exported from the EU ever to reach the public domain.

The investigation found:

- EU countries including the UK notified exports of 81,615 tonnes of banned pesticide products in 2018, with more than half (42,636 tonnes) intended for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs);

- These exports were destined for 85 different countries, of which more than three quarters were LMICs: Brazil, Ukraine, Morocco, Mexico and South Africa were all among the top 10 importers of EU banned pesticide exports;

- Two thirds of the notified exports to richer nations were destined for one place: the US, which has some of the most permissive pesticide regulations among high-income countries and is itself a major exporter of banned agrochemicals to LMICs;

- The products notified for export in 2018 contained 41 different banned pesticides, many of which have been prohibited from use in the EU for more than a decade;

- While the UK was by far the biggest player by volume, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain and Belgium were all major exporters;

- Swiss-based, Chinese-owned Syngenta was by far the biggest exporter of banned agrochemicals among manufacturers, with notified exports of 29,307 tonnes – close to three times those of its nearest competitor;

- But more than two dozen other companies notified banned agrochemical exports from the EU in 2018, ranging from listed multinationals like US-based Corteva Agriscience and Germany’s Bayer, to lesser-known businesses like Italy’s Sipcam Oxon or the UK’s Inovyn;

- As the EU continues to ban pesticides found hazardous to human health or the environment, it is adding to the list of products it produces solely for export: Unearthed and Public Eye found that in 2019 pesticide companies issued their first-ever export notifications for nine recently-banned pesticides;

An EU official told Unearthed that European rules on banned pesticide exports were already “stricter than required” by the Rotterdam Convention. The official said a “ban of exports from the EU will not automatically lead third countries to stop using such pesticides – they may import from elsewhere”.

She argued that “convincing them not to use such pesticides will be more effective” and this would be part of the “green diplomacy efforts” planned by the EU to “achieve more sustainable food systems globally.”

But Nina Holland, a campaigner at the Brussels-based NGO Corporate Europe Observatory, said the European Commission’s goal of reducing pesticide harm in the countries from which it imports food could “only be consistent if a ban on production and export of these pesticides is immediately installed”.

She added: “Apparently the earnings of shareholders of these companies are more important for EU governments than people’s health and the environment in the vast tracts of land that are exploited to produce raw materials for the EU market.

“The fact that this practice is only set to increase, with new chemicals including pollinator-killing substances like fipronil being added to the list, is completely in contradiction with the new Commission’s ambitions when it comes to reducing the harm done by pesticides.”

Fish ‘with two heads’

Among the EU’s most significant exports by weight were the ‘soil fumigant’ 1,3-dichloropropene (1,3-D), and the banned weedkillers atrazine and acetochlor.

Acetochlor, which is produced by both Bayer and Corteva, was banned from EU use in 2011 because of concerns about “potential human exposure above the acceptable daily intake”, “high risk of groundwater contamination”, a “high risk for aquatic organisms” and a “high long term risk for herbivorous birds”.

The chemical is suspected by EU authorities of causing cancer and damaging fertility.

The two multinationals notified exports of more than 4,000 tonnes of acetochlor-based weedkillers in 2018, with most of it coming from Belgium and intended for Ukraine. It is marketed in the former Soviet republic for use on maize, which in turn is one of the main products the EU buys from Ukraine.

Both Bayer and Corteva said their products met high safety standards when properly used, and were tailored to meet the needs of different farmers in different places.

A Corteva spokesperson said: “Crop protection products exported from Europe have been fully approved in the country of destination. These products meet farmers’ agronomic needs in the export countries; these needs will likely differ from the needs of growers in the EU.”

But Dmytro Skrylnikov, head of Ukrainian NGO the Bureau of Environmental Investigation, told Unearthed there was little difference between the environment and pests in Ukraine and parts of the EU. “I believe the climate in Western Ukraine is similar to Poland, which is an EU country, or Slovakia, or Hungary,” he said. “The difference is corrupted government and very powerful transnational corporations.”

Atrazine, meanwhile, has been banned in the EU since 2004 over concerns about groundwater contamination, and has been found by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to pose reproductive and developmental risks to animals and humans – particularly children.

The EU notified exports of 1,425 tonnes of atrazine-based weedkillers in 2018. More than three quarters of the total was notified by Syngenta from France, to destinations including Ukraine, Sudan and Pakistan.

1,3-D is used to kill tiny worms called ‘nematodes’ that live in soil. It has been classified as a likely human carcinogen by the US’s EPA, where the chemical remains controversially used in strawberry fields. However, it was banned in the EU because of concerns about potential risks to wildlife and groundwater from “large amounts” of “polychlorinated impurities”. It is often exported from the EU in mixtures with another banned fumigant pesticide called chloropicrin, which was manufactured as a chemical weapon during World War I.

The bulk of these exports were notified by US-based Corteva from Spain and the Netherlands, and intended for destinations including the US itself, Morocco, Israel, Senegal and South Africa.

But four other countries and at least four other companies also notified exports of these products, with significant destinations including Guatemala and Honduras, where labour rights groups have recently raised concerns about exposure of melon farm workers to the chemical.

Unearthed and Public Eye’s investigation also revealed highly hazardous pesticides exported in smaller volumes. Among these was carbendazim, a fungicide classified by the EU as ‘mutagenic’ – capable of causing gene mutations – and ‘reprotoxic’ – capable of damaging fertility, sexual function or the unborn child.

In Australia, the chemical was at the centre of a high-profile legal battle a decade ago, over claims that spray-drift from macadamia nut plantations had caused a fish hatchery to produce fish with deformities like two heads or no eyes.

EU states issued export notifications for 533 tonnes of carbendazim products in 2018, although German authorities told Unearthed that a planned export of 250 tonnes from their country to Ukraine was not ultimately shipped that year.

The rest of the carbendazim exports were notified from Belgium and France by multinational Arysta LifeScience, now part of UPL, and destined for countries including Bangladesh, Chile, Ecuador, the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, and even Iraq.

Arysta declined to comment for this story.

Agroquimicos de Levante, one of the Spanish companies that exports 1,3-D and chloropicrin, said that although these chemicals were not currently authorised in the EU, new safety studies had been submitted to EU authorities and their status was under review.

Bayer and BASF – along with a number of other pesticide exporters – said they provided large amounts of training on safe use of their products to farmers and dealers in importing countries. Bayer said it provided more than 1 million such trainings last year.

Dutch courage

Bayer’s spokesperson said France’s upcoming ban on the export of banned pesticides would have “no effect on the authorisation or use of the products in question in the countries in which they are authorised” and that France was “the only country in the world which plans for this kind of export restrictions”.

However, a spokesperson for the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management said the Netherlands planned to use an upcoming meeting with other European environment ministers to “explore a European export ban for these substances”.

Unearthed understands that the country is not currently committed to supporting a ban, but wants to explore with its peers whether a ban could be useful.

The spokesperson said an EU or global ban was needed to prevent manufacturers simply switching to other exporting countries in response to national bans.

A spokesperson for the Belgian authorities said France’s decision to ban exports was being “closely followed by our services”. She added that so far Belgium’s three regions had “not yet considered adopting such a measure” but “we very strongly support consideration and adoption of potential measures concerning the export of products whose use is prohibited” in Europe.

Brexit battle

With Brexit looming, any attempts at an EU-wide clampdown on banned pesticide exports would be unlikely to have any immediate impact in the UK. Some even fear leaving the EU could see the UK embrace a larger role in the trade.

“I am concerned that from 1 January 2021 onwards, from which the UK will not be bound anymore by EU rules, the British authorities might be even more willing to allow this dangerous practice,” said Erik Millstone, a food safety policy expert and emeritus professor of science policy at Sussex University.

“What is happening at the moment is a major battle within the UK government between those that want Brexit to be used as an opportunity to weaken regulations, and others who think that it is in the UK’s best interests to maintain high [domestic] standards.”

Regardless of what impact this battle has on UK pesticide exports, the country already exports vastly more banned pesticide than anywhere else in Europe. That is almost entirely down to one chemical and one company.

The 28,185 tonnes of paraquat products that Syngenta notified for export from its Huddersfield factory in 2018 was by itself greater than the total weight of banned pesticides notified for export from Italy, the Netherlands and Germany.

Nearly half of those exports by weight (14,000 tonnes) were destined for the United States – a country where Syngenta is currently facing lawsuits from farmers who allege paraquat gave them Parkinson’s disease.

The bulk of the rest of the notified exports were destined for LMICs like Mexico, India, Colombia, South Africa, and particularly Brazil, where paraquat is used to dry soybean crops and speed up harvest, as well as to kill weeds.

Brazil was the intended destination for 9,000 tonnes of paraquat mixtures from the UK in 2018, despite a 2017 decision by Brazil’s National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) to phase out its use because of the seriousness of occupational and accidental poisoning cases, and scientific evidence of its potential to trigger Parkinson’s and cause gene mutations.

The weedkiller is supposed to be finally banned in Brazil this month, on 22 September. However, soy farmers and other agribusinesses have been scrambling to fund new health research to build a case for reversing the ban. According to Brazillian news reports, ANVISA is due to meet next week to consider whether to delay the ban and give agribusiness more time to complete studies.

Meanwhile, the supposed ‘phase out’ of paraquat in Brazil has had minimal impact on Syngenta’s notified exports to the country. Further documents obtained by Unearthed and Public Eye show that in 2019 the company notified exports of 8,770 tonnes to Brazil, almost identical to the previous year. Even this year, with the ban due to take effect this month, Syngenta planned a further 3,310 tonnes of Brazil paraquat shipments.

A Syngenta spokesperson said the company had a long history of “investing heavily in programs and training to ensure the correct use of our products” and that when “following label instructions, farmers can responsibly and safely use crop protection products that have been authorised by competent local authorities”.

He added: “[It] stands to reason that products required, for example, to grow crops in Indonesia require different solutions to a farmer in France.

“Like farmers’ needs and agronomic conditions, the regulatory systems may differ from one country to the other, so the regulatory status of a specific product is not the same the world over.

“Each country has the sovereign right to adopt and implement regulatory frameworks that best meet its specific needs.”

But Brazilian anti-pesticides campaigner Alan Tygel said many agrochemical manufacturers were involved in intensive lobbying to relax Brazil’s pesticide regulations. “The same companies that say they adhere to national laws, they also work a lot to change and shape these laws,” he told Unearthed. “And that is the main flaw in this argument.”

Campaigners in a number of the tropical countries where Syngenta sells paraquat told Unearthed that it was practically impossible for workers in their countries to follow the label instructions on hazardous pesticides.

Fernando Bejarano, from the Pesticide Action Network Mexico (or RAPAM) said the real consequence of differing climates was that it was too hot in places like Mexico to wear the personal protective equipment available to farmworkers in Europe. “The argument that your use has to follow the label and use the protective equipment is not feasible.”

Many also argued that social inequalities in their countries amplified the risks of these chemicals. “There is an inherent inequality in South Africa in relation to farmers and farmworkers,” said Rico Euripidou, campaigner for South African environmental justice group Groundwork. He explained that farmworkers in South Africa were typically poor migrant workers who spoke native languages, and who were unlikely to have finished school, or to be able to read a label in English, or to understand hazard symbols on a pesticide container.

This combination was a “perfect storm” which led to farmworkers “not being able to take adequate and reasonable measures” to protect themselves.

The only other company that notified a banned pesticide export from the UK in 2018 was Inovyn, a Merseyside-based subsidiary of the chemicals giant Ineos. The company notified an export of up to 4,000 tonnes of 1,3-D to Japan.

An Inovyn spokesperson confirmed that the chemical was intended for a customer that would market it as a pesticide. He said the precise quantity exported was commercially confidential, but it was “certainly below” 4,000 tonnes.

The UK’s department for environment, food and rural affairs declined to comment.

Get stories like this in your inbox every Friday

Sign up to receive weekly and breaking news stories from Unearthed, plus very occasional emails with petitions, campaigns, fundraising or volunteering opportunities from Unearthed or Greenpeace

We promise that we’ll never sell or swap your details and you can opt out at any time – check our privacy policy.

Unearthed and Public Eye spent about nine months filing freedom of information requests for the export notifications used in this investigation. We obtained most of the data from the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), which acts as a kind of clearing house for these notifications in the EU, collecting them from national regulators and sending them to destination countries. But there was too much data to request it all from ECHA, so we also submitted FOI requests to authorities in Germany, Belgium and France.

We obtained a list from ECHA of all of the (52) chemicals that are banned for use as crop protection products and were exported for use as pesticides in 2018, and we attempted to obtain every one of these export notifications. However, many banned products exported from the EU as “pesticides” are not intended for crop protection: they may be used in domestic pest control, to disinfect livestock sheds or medical equipment, or to coat the hulls of ships. Once we obtained the notifications we examined them in detail to identify and remove those that were not intended for crop protection. We encountered a few chemicals on the list that are not generally used in agriculture and were too widely exported to obtain every notification (e.g. ethylene oxide and didecyldimethylammonium chloride). In these cases we took a sample of FOIs, and supplemented this with research in other datasets to ensure they were non-agricultural exports.

Through this process we built a dataset of banned pesticides notified for export as crop protection products. The quantities used in this investigation are those given on the notification forms, which include both the weight of the banned chemical and any other additives to the product.

All countries and companies in our dataset were given an opportunity to review and comment on our findings. The majority declined to comment precisely on numbers, however a few did provide precise figures for 2018 exports: some of these were greater or less than planned. A few others declined to provide precise figures, but did indicate specific exports that did not ultimately take place in 2018. We are publishing a full dataset alongside this investigation which shows in these cases how actual exports differed from planned exports.

The Netherlands told Unearthed that the overall volume of banned pesticides it exported in 2018 was 6,560 tonnes (compared with 8,010 tonnes in the export notifications) but did not provide figures for individual exports. A spokesperson for the Dutch authorities also said that while on paper the Netherlands was the origin of around 2,600 tonnes of exports containing the banned pesticide propargite, in reality “the exported Propargite is produced in Italy and shipped from Italian ports. The firm involved only has an office in the Netherlands for administrative purposes”. Spain said the actual volume of active ingredients it exported in 2018 was 4,025 tonnes, but this is solely the weight of banned chemicals, and cannot be directly compared to the 5,182 tonnes of formulated pesticides it notified for export.