Pesticides are sprayed on a South African wheat farm. The country is one of the biggest markets for pesticides on the African continent. Photo: Dewald Kirsten/Shutterstock

Uncovered: the pesticide lobby’s plan to snatch power over South African science

Tranche of leaked documents reveals attempt by lobby group CropLife South Africa to take over the regulation of scientists who safety-test its members’ pesticides

Uncovered: the pesticide lobby’s plan to snatch power over South African science

Tranche of leaked documents reveals attempt by lobby group CropLife South Africa to take over the regulation of scientists who safety-test its members’ pesticides

Pesticides are sprayed on a South African wheat farm. The country is one of the biggest markets for pesticides on the African continent. Photo: Dewald Kirsten/Shutterstock

A pesticides lobby group representing some of the world’s biggest manufacturers is trying to have itself approved by the South African government as a “scientific body” with the power to licence scientists who safety-test pesticides, leaked documents seen by Unearthed reveal.

This behind-the-scenes manoeuvre by CropLife South Africa – an affiliate of the powerful global pesticides lobby group CropLife International – has provoked an outraged response from the statutory organisation that is legally mandated to accredit South African scientists, according to a joint investigation by Unearthed and the Mail & Guardian, a Johannesburg-based newspaper.

Each year, scientists conduct hundreds of “field trials” across South Africa to test the effectiveness and safety of new pesticide products that companies want to put onto the local market.

These trials are important to pesticides firms. The country is one of Africa’s biggest pesticide markets in itself; but manufacturers also know that having a product approved there means it is likely to be accepted by other countries in the southern half of the continent.

Field trials are also a key part of the safety system intended to protect farmworkers, food shoppers and the environment in South Africa. They are used to determine critical safety questions like how soon farmworkers can be sent back into a field after spraying, or how soon after being sprayed a crop can be harvested and eaten.

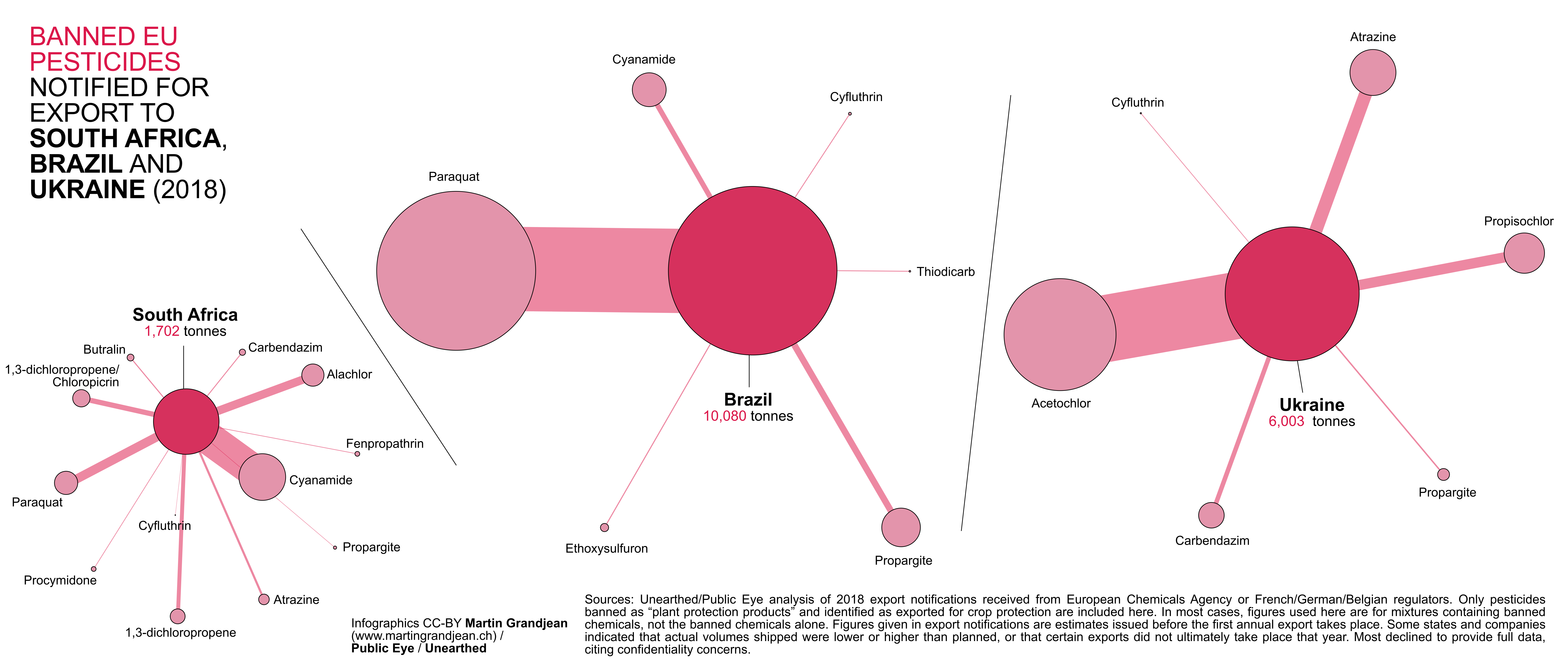

South Africa still allows the use of numerous hazardous pesticides that have been banned in the European Union in order to protect human health or the environment – including chemicals exported from the EU by CropLife-member multinational companies like Syngenta, Bayer and Corteva.

This means the last shred of nominal independence in the regulatory process will be lost

But while South Africa’s pesticides registrar relies upon field trial studies to assess whether products can be approved, the scientists who conduct them are hired by the manufacturers themselves.

In an effort to ensure the quality of this industry data, the pesticides registrar, Maluta Jonathan Mudzunga, is drafting new regulations which are expected to state explicitly that scientists doing these trials must be accredited by a professional scientific body.

But leaked documents show that, in response, CropLife SA has been attempting to position itself as a licencing body for trial scientists, to avoid the need to register its scientists with the statutory professional body, the South African Council for Natural Scientific Professions (SACNASP).

Responding to the investigation, Professor Leslie London, a pesticide expert at the University of Cape Town’s school of public health, said CropLife SA appeared intent on opening “the door for industry scientists who do not register with a professional body to be allowed to submit data for registration purposes”.

“What this means is that the last shred of nominal independence in the regulatory process will be lost”, he said. If a scientist is registered with a professional body, they can be expected to “operate to professional standards” and held to account if they fail to do so.

“If that is not the case, then you have an industry employee who is directly serving industry and there is absolutely no oversight over the quality of their research.

“They can write what they like, and present it as pukka research and nobody will be able to hold them to account if it turns out it is simply fabricated or misrepresenting data.”

Separately, the tranche of leaked documents has also revealed a deal touted by the lobbyists to “embed” consultants paid for by pesticide manufacturers in the office of the pesticides registrar.

A ‘self-regulating system’

The minutes and emails from within CropLife SA show the organisation’s strategy has been to insist that the new regulations allow trial scientists to be registered either with SACNASP, the existing legal body, or with an “equivalent” organisation; at the same time the lobby group has been pressing the registrar to recognise a committee of CropLife’s own members as just such “an independent certification body”.

Volunteers for this proposed committee were selected at a CropLife SA meeting in August 2019. The agreed group included employees of the pesticide multinationals Syngenta, Corteva, and Bayer, others from South African agrochemical companies Meridian Agritech, Philagro and Bitrad Consulting, alongside CropLife SA’s own operations manager Gerhard Verdoorn and its chief executive Rod Bell.

By the spring of 2020, the lobby group believed its plan was on course, the documents suggest. In May, Verdoorn wrote to CropLife SA members telling them that the registrar “agreed that CropLife SA is of sound standing to be a scientific body to accredit trial operators”.

The following month, the registrar, Maluta Jonathan Mudzunga, circulated a draft of his proposed new pesticides regulations, which defined a “suitably qualified person” to conduct pesticide trials in CropLife’s preferred terms: as a person registered with SACNASP “or equivalent”.

But when this document was circulated to SACNASP, it drew a furious response from South Africa’s statutory licencing body for scientists.

SACNASP chief executive Dr Pradish Rampersadh wrote to the registrar in August insisting that “the words ‘or equivalent’ should be removed from the definition”.

He warned: “We submit that should the regulation stand, this will lead to ineffective regulation of the agricultural sciences in South Africa and could lead to a situation in which the Council may be required to prosecute the individuals concerned if they were to practise without being registered with SACNASP.

“SACNASP is mandated as the statutory body with the primary role of regulating the natural scientific profession in terms of [South Africa’s Natural Scientific Professions Act].”

He added that he had already written to the South African department of agriculture, land reform and rural development (DALRRD) to say pesticide trials must be conducted by SACNASP-registered scientists.

CropLife and the corporations it represents continue to market highly hazardous pesticides in South Africa that are banned in other countries

And he warned that the proposal that CropLife SA itself be able to certify scientists as qualified to conduct these field trials was “in contravention” of South African law.

In response, Mudzunga produced a new draft, stating that all trial scientists must be registered with SACNASP. CropLife, however, has not given up.

The leaked documents reveal an angry response from the pesticide lobby. In late October, CropLife SA wrote to the registrar complaining: “In our humble opinion, listing only SACNASP will exclude a vast number of people from participating in our industry and could indeed be challenged from a point of being ‘anti-competitive’.”

In a statement to the Mail & Guardian, SACNASP chief executive Dr Rampersadh confirmed this dispute was ongoing.

“SACNASP has engaged with the competent authority to ensure that the requirements of the Natural Scientific Professions Act 2003… are complied with by all those who undertake natural science work, including those in the agricultural sector,” he said.

“Discussions are ongoing with the Registrar and CropLife to pursue all avenues for an amicable resolution, to ensure that SACNASP is able to fulfil its mandate to the public and to government.”

Mudzunga, the registrar, said it had been the department of agriculture’s position for several years that people generating data for pesticides registration should be “regulated by a professional scientific body”. This decision, he explained, had led to “discussions and counter proposals”.

“One was that, other than SACNASP, is there any other independent professional body that we can explore?” he said. “Remember this professional body must be independent of whoever is being regulated.

“There has been the proposal that we must then consider SACNASP together with some equivalent, and, this equivalent, there has been a discussion as to how it must look like.

“So, there have been documents CropLife has put in place about this. Again, the issue is, will that meet [the requirement for] the independence of that body? We have indicated in a later review of the regulations we’ve published that this body currently must be SACNASP.

“Of course, now there are discussions about whether it should only be SACNASP, and that’s where the discussions are now.”

CropLife SA chief executive Rod Bell said the organisation “continuously strives to raise the scientific standards of the crop protection industry” and because of this “a draft CropLife SA certification scheme was proposed for technical employees of CropLife SA member companies”.

He said this was done in response to a request from the registrar “to validate field trial data”, and a request from CropLife members for “an opportunity for their employees to become part of a self-regulating system for technical people of CropLife SA member companies”.

He suggested this proposed scheme was an “entirely separate matter” to the draft pesticide regulations circulated by the registrar.

And he said that “CropLife SA absolutely refutes the accusation or statement that it is attempting to create or find a loophole for regulatory processes” with its proposals for those regulations.

“CropLife SA does, however, question the need for all persons to be SACNASP registered in order to do their job in the industry, hence the ongoing interaction with SACNASP,” he added.

“Until clarity is obtained from the ongoing interactions with SACNASP, we have the responsibility to ensure that a blanket clause in the draft regulation… does not unfairly exclude any persons currently working in the industry and prevent them from executing their functions.”

‘Fox in charge of the henhouse’

But Rico Euripidou, of the South African environmental justice group groundWork, said it sounded like CropLife SA was “lobbying hard to position themselves as ‘the fox in charge of the henhouse’”.

If successful, he warned, CropLife SA’s move “would essentially undermine the independence of our regulatory ability on minimising the harms of chemical use, including the risks associated with highly hazardous pesticides, many of which are produced by CropLife members such as Bayer Crop Science, Syngenta, BASF and Corteva Agriscience.”

Campaigners argue this is part of a wider trend towards what Euripidou called an “outsourcing of our democracy to consultants and corporates, who define how decision-makers hear our voices and how we regulate important issues such as pesticides use in South Africa.”

He added that this was not only happening in South Africa, but also on an international scale. He pointed to a recently-signed partnership deal between CropLife International and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

Last month, 352 civil society and Indigenous People’s organisations from across 63 countries wrote to the FAO calling on it to reconsider this agreement.

Euripidou’s concerns were echoed by Vanessa Black, research and policy coordinator at NGO Biowatch South Africa.

“Civil society already has grave misgivings about the regulation and monitoring of agrichemicals in South Africa given the evidence of their misuse from affected farm workers and the public,” she said. “Any review of the pesticide regulations should first and foremost consult with those most affected.”

She added: “CropLife and the corporations it represents continue to market highly hazardous pesticides in South Africa that are banned in other countries.

“Biowatch SA calls on our Department of Agriculture to stand up against this corporate lobbying and protect our health and our food system from increasing corporate control.”

Amy Giliam, branch manager of the African Climate Reality Project, said exposure “to highly hazardous pesticides, as is the case in South Africa”, was linked to “cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, hormone disruption, developmental disorders, and sterility”.

She added that runoff from pesticides contaminated soil and groundwater, decreased soil fertility, and contributed to biodiversity loss, including the loss of beneficial insect populations like honey bees. “All of these combined can lead to a large decline in crop yields which is a threat to food security.”