UK oil and gas emissions intensity rises to record high

After years of cutting emissions per barrel of oil extracted, UK drillers saw carbon intensity rise by 15% in 2021

UK oil and gas extraction released more carbon dioxide per barrel last year than it has for several years, according to an Unearthed analysis of industry data.

The data, from Norwegian oil intelligence service Rystad Energy, shows that the carbon intensity of UK oil and gas drilling had improved from 2018 to 2020, albeit marginally.

In 2021, however, the industry’s upstream CO2 emissions intensity is estimated to have jumped 15%, rising by approximately 3kg of carbon dioxide per barrel of oil equivalent (boe) to 23kgCO2/boe — higher than at any point since the industry regulator began monitoring the metric in 2016. Experts say the increase was at least in part due to pipeline outages.

It comes as the UK has recently approved a new oil and gas field off the coast of Scotland, weeks after hosting the COP26 climate summit.

The figures refer to the amount of carbon dioxide released to get a barrel of oil out of the ground, before any of it is burned.

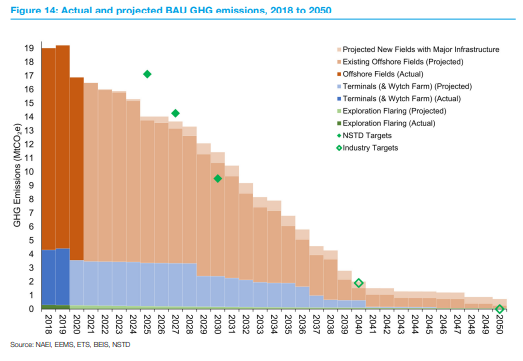

Industry targets

Despite the unprecedented rise in carbon intensity, the sector’s absolute emissions continued to fall. The sector’s operational CO2 emissions dropped 0.7 million tonnes last year to an estimated 11.5 million tonnes — roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of 2.5 million cars.

The carbon intensity backslide follows a raft of new targets announced by the government early in the year, which require drillers to reduce operational emissions 10% by 2025, 25% by 2027 and 50% by 2030.

The Oil and Gas Authority (OGA), a government agency that oversees the industry, expects the interim goals to be met through “existing abatement initiatives and installations ceasing production,” but said “more drastic” initiatives are required in order to meet the 2030 target.

Thom Allen, an oil and gas analyst at climate think tank Carbon Tracker, told Unearthed: “As operational emissions account for less than 15% of total emissions from oil and gas production and usage, the industry’s focus on these targets is misguided.”

“To stay within the finite limits of the global carbon budget, consumption and therefore production, will need to rapidly fall. Thus, while companies should of course look to reduce the climate impact of their operations, a focus on operational emissions intensity targets only addresses a small part of the fundamental risks posed to the upstream industry by the energy transition.

Older oil fields

The carbon intensity of UK oil and gas extraction compares unfavourably to many countries from which the UK imports its oil, gas and LNG (liquefied natural gas), although LNG has significantly higher associated emissions due to the liquefaction process and transport.

In the US, oil and gas extraction produces half the emissions per barrel (11kg/boe) and in Norway it’s even less (7kg/boe).

International comparisons, however, are hard to make, partly because gas tends to be less carbon intensive than oil so countries which produce more gas have lower carbon intensity. The US has a higher share of gas production than the UK.

However, even taking this into account, the UK’s carbon intensity is high by international standards, and especially high in comparison to its immediate neighbour Norway.

“The UK has more production from mature fields, which is generally a huge driver [of higher emissions intensity] – as the reservoir gets depleted it gets more challenging to get the barrels out of the ground and typically it requires more pressure support and injection activity,” Rystad analyst Jon Erik Remme told Unearthed.

“The UK also has far more liquids production than gas, and oil is generally more energy-intensive than gas,” he added.

Why did the UK see a surprise uptick in carbon intensity last year? Remme believes it might have something to do with reduced production from the UK’s North Sea reserves due to months-long maintenance work on a key pipeline.

“In terms of 2021 specifically, the maintenance of the Forties system is naturally a key event which effectively reduced overall production from the UK continental shelf. This also partly explains the estimated increase in upstream CO2 intensity – in 2022 we expect intensity to be back to 2020 levels.”

Flaring

Another reason why extracting UK oil and gas is so carbon intensive is flaring, a process in which operators set alight unwanted natural gas into the atmosphere.

Flaring accounted for 3kg per boe of the total CO2 intensity in 2021, the same as it has done the previous year and 1kg better than in prior years — but in Norway the practice has been banned for decades. Labour has called for flaring to be banned in the UK.

Last year Unearthed revealed that North Sea oil companies are releasing the equivalent of a coal power station’s worth of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere every year through flaring.

Sometimes flaring is carried out for safety reasons but more often it is an attempt to save money by getting rid of gas considered unprofitable to transport back to shore.

The OGA recently announced new guidance that calls for flaring, venting and associated emissions to be released “at the lowest possible levels,” zero routine flaring by 2030 and all new developments to be planned and developed on the basis of zero routine flaring.