A bee on honeycomb in the Netherlands, one of more than a dozen countries across the EU still exporting banned neonicotinoid pesticides to the Global South. Photo: Bas Beentjes/Greenpeace

EU sending huge quantities of banned, bee-killing pesticides to poorer countries, documents reveal

Investigation shows for first time the full scale of the EU’s trade in neonicotinoids it has branded a global threat to biodiversity and food security

EU sending huge quantities of banned, bee-killing pesticides to poorer countries, documents reveal

Investigation shows for first time the full scale of the EU’s trade in neonicotinoids it has branded a global threat to biodiversity and food security

A bee on honeycomb in the Netherlands, one of more than a dozen countries across the EU still exporting banned neonicotinoid pesticides to the Global South. Photo: Bas Beentjes/Greenpeace

The European Union is exporting more than 10,000 tonnes of ‘bee killing’ neonicotinoid pesticides a year to poorer countries, despite having banned the use of these chemicals in its own fields to protect pollinators.

That is the key finding of a new investigation by Unearthed and Public Eye, which reveals for the first time the full scale of Europe’s continued trade in banned ‘neonic’ pesticides.

Documents obtained under freedom of information laws show that in 2021 EU companies issued plans to export more than 13,200 tonnes of banned insecticides containing around 2,930 tonnes of the neonicotinoid active ingredients thiamethoxam, imidacloprid or clothianidin.

We consider it an act of aggression, of ecocide, to sell toxic substances that are highly dangerous to pollinating insects

– Pedro Kaufmann, Argentinian Beekeepers Society

This is the first time it has been possible to track a full year’s worth of these exports since the EU prohibited all outdoor use of these chemicals on its own farms in 2018.

Scientists and campaigners described the scale of the trade as “astonishing” and called for an immediate end to the EU’s “unacceptable and immoral” exports of pesticides banned for EU use.

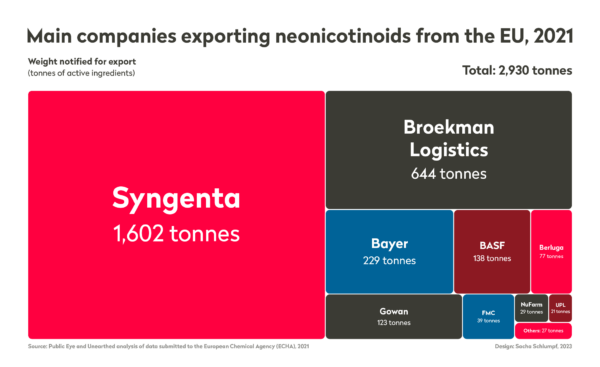

Unearthed and Public Eye identified 17 companies involved in the export of banned neonics from the EU, with by far the largest exporter being the Swiss-headquartered, Chinese-owned pesticides giant Syngenta. Planned exports by Syngenta subsidiaries accounted for more than three quarters of the EU total, and included an export to Brazil of enough insecticide to spray the entire surface area of New Zealand.

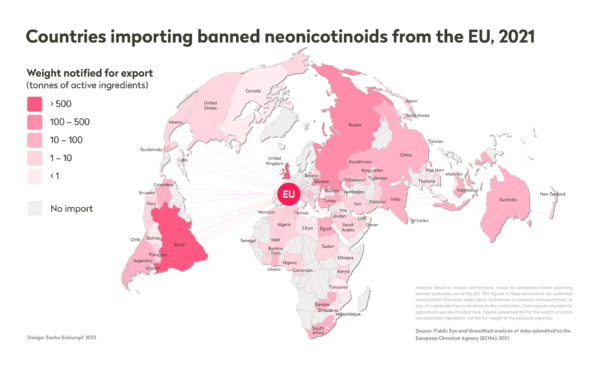

The overwhelming bulk of the EU’s banned neonic exports – 86% by weight – was destined for low- or middle-income countries (LMICs), where UN agencies say hazardous pesticide use tends to pose the greatest risks.

By far the biggest of these importers was Brazil, a country that is thought to be home to as much as 20% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. But companies also issued plans to export to dozens of other LMICs, including Ukraine, Indonesia, South Africa and Argentina.

“Humanity depends on ecological balance, the maintenance of biodiversity and the health of people in all countries,” said Karen Friedrich, a researcher at Brazil’s Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), an institute for research on science, technology and health.

The EU would not be consistent in its ambition for a toxic-free environment if hazardous chemicals that are not allowed for use in the EU can still be produced here and then exported

– Environment commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius

“Therefore, besides being unjust, the export of pesticides that are banned in your territory is unwise, because the damage will also be felt in the European Union.”

In Argentina, one of the top five destinations for the EU’s banned neonic exports, beekeepers estimate they have lost 30% of their hives in the past decade.

The Argentinian Beekeepers Society (SADA, from its initials in Spanish) called on the EU to “immediately stop the production of these highly hazardous chemicals”.

“We consider it an act of aggression, of ecocide, and a violation of human rights to sell toxic substances that are highly dangerous to human health and pollinating insects,” SADA secretary Pedro Kaufmann told Unearthed and Public Eye.

Neonicotinoids, he added, are a “serious threat to our food security” that are “devastating the world’s pollinator population” and causing environmental damage “of a magnitude that is still difficult to grasp”.

Worldwide decline

More than three quarters of the world’s leading types of food crops depend on pollinators, mainly insects. This year, scientists published a study estimating that the global loss of pollinator populations is already causing about half a million early deaths annually by reducing the supply of healthy foods.

The EU itself considers neonics to pose such a grave threat to biodiversity and food security that it has just passed a law that will ban the import of foods containing all but the lowest detectable traces of thiamethoxam or clothianidin.

This law, passed in February, says there is “a substantial body of evidence showing that active substances which are neonicotinoids, such as clothianidin and thiamethoxam, play an important role in the decline of bees and other pollinators worldwide”.

Because this is an “international concern”, it continues, the EU needs to take steps to protect pollinators worldwide from the risks of these chemicals: “Preserving the pollinator population within the [EU] only would be insufficient to reverse the worldwide decline of pollinator populations and its effects on biodiversity, agricultural production and food security.”

Despite its stance, the EU continues to ship thousands of tonnes of these same banned neonics overseas each year. Under current EU law, when the use of a chemical is banned because of the risk it poses to health or the environment, companies remain free to manufacture and ship it to countries with more-permissive regulations.

The European Commission this month launched a consultation on possible measures to ensure that “hazardous chemicals banned in the European Union” are no longer “produced for export”.

Launching the consultation, environment commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius said the EU “would not be consistent in its ambition for a toxic-free environment if hazardous chemicals that are not allowed for use in the EU can still be produced here and then exported”. These chemicals, he added, “can cause the same harm to health and the environment regardless of where they are being used”.

This chemical colonialism is invisible, it is silent and it has spread in our soils, in our bodies, in our water

– Larissa Bombardi, geography professor, University of São Paulo

The Commission committed in 2020 to bring forward concrete proposals to end this practice, shortly after the publication of an earlier Unearthed and Public Eye investigation on banned pesticide exports.

However, the strategy faces staunch opposition from the chemicals lobby, and campaigners fear the proposals will come too late to be made law before the next European elections in 2024. It also remains unclear what the scope of the Commission’s proposals will be.

Unearthed and Public Eye’s investigation identified more than a dozen different companies exporting banned neonics from the EU, including the giant multinational pesticide companies Syngenta, Bayer, and BASF. Those who commented for this story said they believed their products were safe for bees when used as intended, that pesticides were vital for protecting crop yields, and that while these neonics were banned in the EU they remained licensed in many countries around the world.

Some also said a ban on the export of banned pesticides would be “counterproductive”, or argued that countries should be free to make their own decisions about which chemicals are right for their own farmers.

“In our opinion, countries should decide for themselves and sovereignly which crop protection products are needed for their local agriculture instead of imposing a unilateral trade ban,” said a spokesperson for the German agrochemical giant BASF. “We believe that an export ban does not help those it is intended to protect.”

He argued that a lack of “carefully tested” pesticides in importing countries could lead to “unsafe harvests” for farmers. Conversely, he added that if Europe banned these exports then farmers in importing countries could simply replace them with “the same or similar products” produced in other places with “lower safety standards”.

Campaigners in importing countries countered that a European export ban would send a “very important signal”, creating pressure for other exporting nations to follow suit. They also argued that importing countries in the Global South were often not in a strong position to assess and manage the dangers of hazardous pesticides.

“Unfortunately, LMICs often lack the resources to evaluate and enact regulations to ban these pesticides,” said Sarojeni Regnam, executive director of the Pesticide Action Network Asia Pacific campaign group. “Or even if they are banned, they lack the ability to monitor and enforce these bans. These hazardous pesticides are mostly used by farmers and agricultural workers in conditions of poverty, and [who have] a lack of awareness of their dangers.”

‘Chemical colonialism’

Unearthed and Public Eye found that Syngenta notified exports of more than 10,400 tonnes of thiamethoxam-based insecticides from the EU in 2021, to 61 different countries.

However, more than half of that weight came from a single planned export to Brazil of 5.9 million litres of the company’s blockbuster pesticide Engeo Pleno S – enough to spray the entire surface area of New Zealand. A previous investigation by Unearthed and Public Eye found that thiamethoxam-based insecticides were by far Syngenta’s bestsellers in Brazil, with sales worth well over $200m in 2018.

Brazil is home to some of the most biodiverse areas on earth, but enormous export-driven plantations of soya, maize, and sugarcane have turned it into the world’s biggest market for highly hazardous pesticides.

“While classic colonialism was conducted through physical violence, such as deforestation, expulsion of indigenous peoples and so on, now we are facing a more cruel and perverse form of colonialism,” said Larissa Bombardi, a professor of geography at the University of São Paulo and expert in Brazilian pesticide use. “Because this chemical colonialism is invisible, it is silent and it has spread in our soils, in our bodies, in our water.”

She added that bees were dying in Brazil, and this indicated that “other pollinators are also dying”: “This is one of the main threats to our biodiversity.”

We are already in the sixth mass extinction event, with species going extinct at over a thousand times the natural rate. Unless we take this crisis seriously, we face a collapse of global ecosystems

– Dave Goulson, biology professor, University of Sussex

Over a five-year period running to the end of 2017, beekeepers responding to an online survey reported the loss of 19,296 colonies and nests across Brazil, representing the death of more than a billion bees.

In 2019, the BBC reported the death of more than 500 million bees in Brazil in just three months, with researchers blaming exposure to neonicotinoids and the insecticide fipronil.

A scientific study published earlier this year found that Brazil’s indigenous species of stingless bees may be even more sensitive to thiamethoxam than honeybees.

A spokesperson for Syngenta said: “Our products are safe and effective when used as intended. Wherever we operate, we do this in full compliance with local laws and regulations.”

He added: “While some of our products may not be registered for use in the EU, they are safety assessed, registered, and allowed in the countries where they have been approved for import, reflecting the different weather, pest and disease pressure and farmers’ need.”

Sixth mass extinction

Many of the companies exporting banned neonic products from the EU told Unearthed and Public Eye they believed their products could be used without unacceptable risk to bees, and that different countries had different climates and pests, requiring different pesticides.

Among them was the German agrochemical giant Bayer, the EU’s main exporter of the neonicotinoids clothianidin and imidacloprid. Bayer notified exports of banned products containing these chemicals to 51 different countries in 2021, including Ukraine, Indonesia, Guatemala, Togo, and Kenya.

“Bayer is committed to safe and sustainable use of its products and neonicotinoids have a long history of safe use if used according to label instructions,” said a Bayer spokesperson. “They are among the most intensively researched substances in the world.”

He suggested the differing “safety ratings” given to insecticides in different parts of the world reflected “the local needs of farmers” and added that Bayer supports “approval processes that follow high science-based standards.”

But scientific experts on the impact of pesticides on biodiversity rejected the suggestion that these neonics could be used safely.

Jean-Marc Bonmatin, a specialist on pesticide exposures at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and vice-chair of the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides said the threat posed to pollinators by neonicotinoids was “huge”.

“It is similar in intensity to that of climate change, in terms of its impacts, and it’s progressing even more rapidly,” he told Unearthed and Public Eye.

The decline of pollinators needed to be addressed at a “global scale”, without forgetting that it is often “the poorest countries which are the richest reservoirs of biodiversity”.

“While there are many causes for the collapse of pollinators, pesticides have a major share of responsibility – neonicotinoids in particular. The question is no longer to list all the causes of the decline, but to act quickly and forcefully to limit its extent.”

University of Sussex biology professor Dave Goulson, an expert on the ecology of insects, said the world was “already in the sixth mass extinction event, with species going extinct at over 1,000 times the natural rate”. Unless we take this crisis seriously, he added, “we face a collapse of global ecosystems”.

He told Unearthed and Public Eye there were “many hundreds of scientific studies showing that neonicotinoids threaten pollinators and entire ecosystems” and it was “absolutely unacceptable and immoral” for the EU to continue exporting banned neonics to poorer countries.

“If neonicotinoids are too dangerous to use in Europe, they are too dangerous to use anywhere. Many of these countries have vastly greater biodiversity than Europe.”

He added that the quantities of banned neonics being exported from the EU were “astonishing”.

Unearthed and Public Eye found that agricultural insecticides notified for export from the EU in 2021 contained an estimated 2,930 tonnes of the banned neonic active ingredients thiamethoxam, imidacloprid or clothianidin.

“Peak neonicotinoid use in the UK before the ban was 110 tonnes per year, and that was enough to impact on butterflies and wild bees,” said Goulson.

Plans for bans

Currently, the main EU law regulating the export of banned chemicals is the “prior informed consent” (PIC) regulation. Under this law, EU companies need to issue an “export notification” for the importing country any time they intend to export a product containing a banned chemical.

These documents detail the amount the company intends to send, the reasons the product is banned in the EU, and its intended use in the destination country.

Export notifications are not a perfect record: if an export is approved the company is free to ship more or less than the amount declared on the notification, and sometimes the export does not take place at all. But they are the most precise paper trail that exists for the EU’s trade in banned pesticides.

The banned neonics became subject to the PIC rules in late 2020. Over seven months last year, using freedom of information requests, Unearthed and Public Eye managed to obtain every notification issued in the EU for banned agricultural neonic exports in 2021.

This is the first full year for which this data is available.

The investigation identified 13 different countries across the EU that issued export notifications for banned neonic products in 2021, but by far the biggest exporters by planned weight were Belgium, France, Spain and Germany. Other countries that played a significant role in the trade that year were the Netherlands, Austria, Hungary, Greece and Denmark.

Spokespeople from the governments of exporting countries including Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark told Unearthed that they supported an EU ban on the production of banned pesticides for export.

“The European application of a ban of clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam was an important step towards the protection of pollinators,” said a spokesperson for the German federal ministry of food and agriculture. “However, further efforts will be required in order to farm in a more resource-conserving manner in the future.”

Some of these countries have already started taking steps to clamp down on these exports at a national level. In 2022, France became the first country in the EU to impose a national ban on the export of banned pesticides. A previous investigation by Unearthed and Public Eye found that French exports of neonicotinoids dropped sharply in response, but were not stopped entirely. Belgium and Germany are both also in the process of instituting export bans for certain banned pesticides, although the German ban is focused on those pesticides that are harmful to human health. However, other countries told Unearthed and Public Eye that the issue needed to be tackled at an EU-wide level, or companies would simply be able to switch their exports to other member states in response to national bans.

“A national ban would have only a limited effect,” said a spokesperson for the Dutch ministry of infrastructure and water management. “It would risk only changing the port of departure rather than ending the export as such.

“Therefore, the Netherlands strongly supports EU-wide measures, as such measures would be far more effective.”

In total, 17 different companies issued export notifications for banned neonics that year, with the planned weight totalling 13,274 tonnes. The estimated weight of neonicotinoid active ingredients in these exports was 2,930 tonnes.

We cross-referenced these figures with public summary export data where possible to confirm that they correlated in overall scale. The overall amount of neonics exported from the EU in 2021 was greater than the amount identified in our investigation, largely because our investigation focussed only on products being exported for banned agricultural purposes. Other neonic products are exported for purposes that are still legal in the EU, such as imidacloprid flea collars. We excluded these export notifications from our calculations, and focussed solely on exports of products that are banned from EU use.

The five main exporting companies accounted for 95% of agricultural neonic exports by weight. By far the biggest of those was Syngenta, which alone accounted for 79%. Other companies in the top five included the German-based multinationals Bayer and BASF, the US-based pesticide company Gowan, and a Dutch company called Broekman Logistics, which runs a hazardous goods warehouse in the port of Rotterdam.

All the exports arranged by Broekman, which did not respond to requests for comment, were either Syngenta products or shipments of pure thiamethoxam, the active ingredient in Syngenta’s banned neonics.

A spokesperson for Gowan said it did not ultimately export any banned neonics from the EU under the licences identified by Unearthed and Public Eye’s investigation. He added: “We do not believe that the science or data available support the conclusion that imidacloprid or other neonicotinoids should be banned.”

Unearthed and Public Eye offered companies and countries the opportunity to provide precise data on the amount of banned neonics they ultimately exported in 2021. Most declined to do so.

The Netherlands confirmed that in that year it shipped agricultural exports containing a total of 1,695 tonnes of the banned neonic thiamethoxam, to countries including Cuba, Zambia, and Switzerland. This was more than double the country’s planned exports for that year, of 644 tonnes. However, a planned export to Uzbekistan did not take place.

Denmark notified banned insecticide exports in 2021 containing around six tonnes of imidacloprid. A spokesperson for the Danish environment ministry told Unearthed that the country ultimately shipped more than double this amount – 13.3 tonnes – to Colombia and Israel. However, planned exports to Ecuador and Palestine were not shipped.