Agriculture is the leading source of the powerful greenhouse gas methane globally. Photo: George Rose, Getty Images.

How the beef industry is trying to change the maths of climate change

A new metric for the greenhouse gas methane could see the agricultural sector claim to be climate neutral without significantly cutting emissions

How the beef industry is trying to change the maths of climate change

A new metric for the greenhouse gas methane could see the agricultural sector claim to be climate neutral without significantly cutting emissions

Agriculture is the leading source of the powerful greenhouse gas methane globally. Photo: George Rose, Getty Images.

Fresh off the heels of a major methane ‘win’ at the Glasgow climate summit, the American beef lobby is leading a global effort to change how the climate impact of the powerful greenhouse gas is measured.

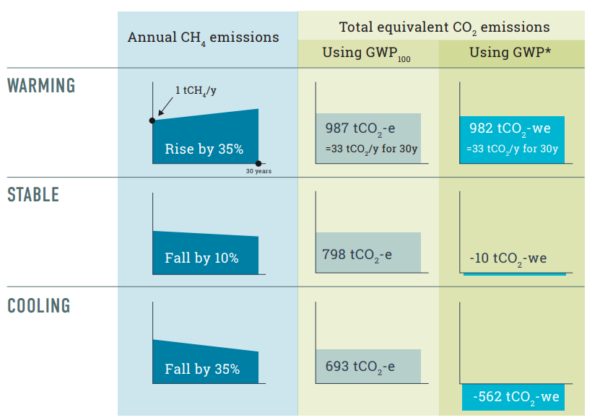

The industry is rallying around a new metric – known as global warming potential star (GWP*) – that some experts fear could be used to undermine global climate efforts by enabling big polluters to claim they are climate neutral without significantly cutting emissions.

Last month, at an industry summit in Houston, Texas, the chief executive of leading lobby group the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association (NCBA) said GWP* “is the methodology we need to make sure everybody is utilising in order to tell the true story of methane” and described how the NCBA “spends time on Capitol Hill making sure that our government recognises it.”

“We’re also part of the International Beef Alliance,” he continued, “we’re working with our partners around the globe to ensure that everybody is working towards adoption of GWP*.”

The International Beef Alliance is comprised primarily of meat trade associations from North America, Latin America and Australasia. The NCBA represents over 175,000 cattle producers, and major food companies such as Cargill, Tyson Foods and McDonalds sit on its product board. It declined to respond to this story.

The NCBA is not alone in pushing for this climate maths rethink. In 2020, farming unions from the UK and New Zealand signed a joint statement calling on the IPCC to start using the metric in its reports.

Ben Lilliston, director of climate change at the Institute of Agriculture and Trade Policy, told Unearthed: “How we account for methane emissions has very real implications for the meat and dairy industry – and the planet. The global methane pledge makes clear we need to reduce methane emissions sharply and there are real opportunities to do that in agriculture.

“But if the big meat and dairy companies control the methane accounting debate in order to mask their emissions, it takes our eye off the factory farm system these companies prefer and we won’t get the emission reductions we need.”

Global warming potential

The methane issue has taken on new salience in light of developments over the past year. Not only are atmospheric methane levels climbing ever higher, but scientists recommend making rapid emission cuts to stave off near-term warming.

At COP26 the US and EU led a global pledge to reduce methane emissions 30% by 2030, although no concrete demands were made of the primary polluter – agriculture.

The way the world currently tracks the impact of various greenhouse gases is a methodology called global warming potential 100 (GWP100), which measures the heat absorbed by gases over the course of 100 years.

Using this method methane has a global warming impact nearly 30x greater than CO2. Under another commonly used metric, GWP20, which measures the heat absorbed over 20 years, its warming potential is even greater: more than 80x that of CO2.

Methane, however, does not stay in the atmosphere like carbon dioxide does — it lasts about 12 years before breaking down into water and carbon dioxide, which still causes warming, but at a much lower level.

The GWP100 method is an approximation, and it overstates the impact of existing methane sources by a factor of 3-4 over a 20-year time horizon whilst understating the effect of new emissions by a factor of 4-5.

That short atmospheric half-life has led some to argue that rapidly reducing methane emissions could “buy time” for the world to act on long term fossil fuel emissions by slowing down catastrophic warming in the short term. Cutting methane could even have a cooling effect.

Using GWP20, as some experts are calling for, would capture the urgency of preventing forest fires, floods and migration – but it could have serious implications for agriculture.

And so industry lobby groups are increasingly supporting another metric developed a few years ago by leading climate academic Professor Myles Allen and a team of scientists at the Oxford Martin School.

The method, known as GWP*, reflects changes in the amount of methane entering the atmosphere; its adoption would push policy towards avoiding new sources of methane whilst rewarding even small overall reductions.

Allen told Unearthed under GWP* “any new methane source has a 16x larger global warming impact per tonne of methane emitted than an established source (more than 20 years old).”

But though the science underpinning the metric is not controversial, its application is.

‘Unethical consequences’

The metric could be used to maintain current atmospheric methane levels – rather than trying to reduce them – and it could punish new sources of methane in the global south over existing emitters in the west, such as the American meat industry.

Dr Joeri Rogelj, director of research at the Grantham Institute at the London School of Economics, told Unearthed that moving to GWP* could have “unethical consequences” such as rewarding historic emitters and putting developing countries at an unfair disadvantage.

“By picking GWP*, countries or sectors that are emitting a lot of methane could claim credit or rewards while continuing to pollute, albeit a little less,” he said. “At the same time, countries in the south that are gently increasing their national emissions for development would be severely penalised. Using GWP* as suggested by some industries today can therefore go directly against the idea of climate justice or international fairness.”

To that, Allen said: “That’s just the way it is, whether the new source is for a worthy cause, like a farmer in a developing country, or a less-worthy one, like a dodgy fracking operation. We can’t design metrics to favour specific policy outcomes: they exist to inform policy, not to dictate it, and bad metrics (like GWP100) simply cause confusion.”

Net zero

In 2019, one of Allen’s team – Dr Michelle Cain, now at Cranfield University – wrote that if New Zealand farmers were to cut their methane emissions by 24% then, under GWP*, the country “could declare itself climate neutral almost immediately, well before 2050, and only because farmers were reducing their methane emissions.”

“That’s a free pass to all the other sectors, courtesy of New Zealand’s farmers,” she concluded.

And herein lies the other serious controversy over GWP*: its application could change the meaning of climate neutrality and consequently undermine the integrity of the Paris Agreement.

It’s certainly what NCBA lobbyists suggested at the meat summit when its President Don Schiefelbein said it’s “going to be pretty easy to” become climate neutral by 2040 “without reducing the number of cattle.”

GWP*, he said, “would speed up the ability to meet this part of the goal that we have in carbon neutral by 2040.”

To Rogelj, this represents an erosion of the Paris Agreement’s ambition. “If net zero greenhouse gas emissions is redefined using GWP* it would mean global warming is not projected to decline but rather flatten out instead.

“Simply changing the metric to GWP* would thus erode the climate ambition of the Paris Agreement, potentially achieving the opposite of what the world needs today.”

John Lynch, another Oxford academic in the GWP* team, argues that the existing definition of net zero – ie no emissions – is virtually impossible for the livestock industry to achieve.

“I imagine ruminant producers do not see how they can achieve this, as it does not look plausible that ruminant methane will be brought sufficiently low or that enough affordable CO2-removal will be around to offset the remaining methane.”

Allen said: “It would clearly be helpful if the agriculture industry were to reduce its methane emissions: if they can do so faster than 3% per decade, then they will be compensating for ongoing warming caused by other gases.”

“And if we were to treat all actions equally in terms of impact on global temperature, then they would be rewarded for doing so, just as they would if they were to help reduce global warming by planting trees.”

The GWP* conversation needs to be had, according to Lynch, however complex and contentious it could be.

“What I really think we need is an open debate about these factors and the type of climatically sustainable future we want.”