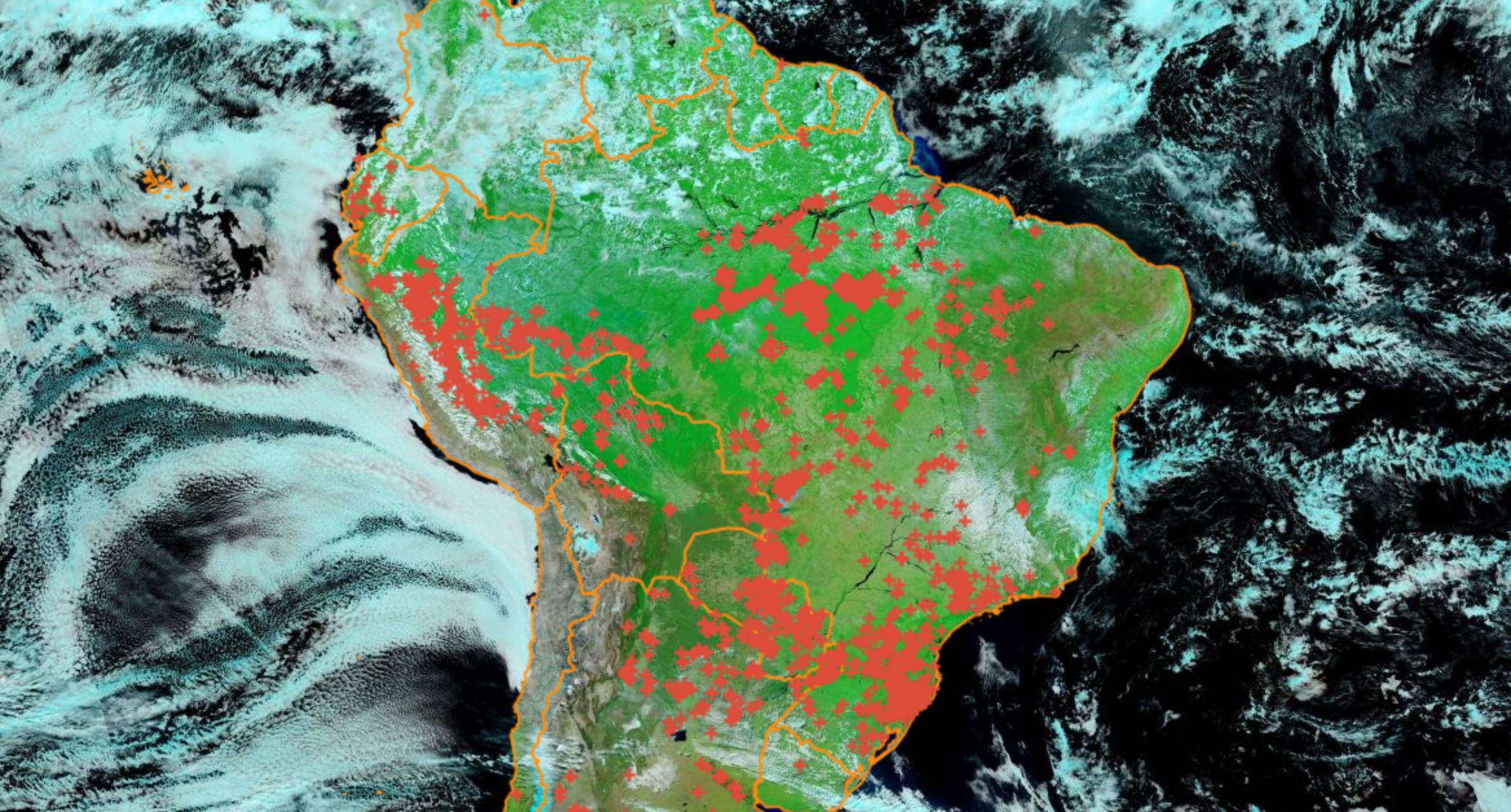

An area of burnt forest is seen in Amazonas state in August 2019. Photo: Vinícius Mendonça/Ibama

August’s fires in the Amazon are at their highest levels in a decade

Drought, the pandemic, and tacit political support for deforestation threaten a 'catastrophic' burning season

August’s fires in the Amazon are at their highest levels in a decade

Drought, the pandemic, and tacit political support for deforestation threaten a 'catastrophic' burning season

An area of burnt forest is seen in Amazonas state in August 2019. Photo: Vinícius Mendonça/Ibama

Fire season has kicked off early and with worrying intensity in the Amazon, with the worst start to August in a decade. Protected areas in particular have seen an increase in blazes over the past ten days, analysis of official data by Unearthed has found.

Deforestation also continues to accelerate, raising fears that the coming months could bring catastrophic damage to the region.

Amazonian forest loss in the year to July was 9,205 sq km, data from INPE, Brazil’s space agency, showed – a third higher than the previous year and the equivalent of more than two football pitches cleared every minute.

Fires in the Amazon last year prompted an international outcry, burning so fiercely and widely in August that drifting smoke turned the afternoon skies above Sao Paulo, 2,500 km from the forest, dark as night. Now experts say the triple threats of unchecked deforestation, tacit support from the Bolsonaro administration and drier than usual weather could trigger an even worse environmental crisis in the coming months.

Deforestation and fires inhibit the capacity for tropical forests to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The Amazon is a globally important carbon sink, but studies suggest that as fires accelerate and pump out thick plumes of carbon dioxide-laden smoke, the region could be at risk of transformation to a net carbon source, causing an acceleration in climate breakdown.

The first ten days of August saw 10,136 hotspots across the Amazon biome, 17% higher than the 8,669 hotspots registered last year. Data from INPE, Brazil’s space agency, shows it was the the highest number for the beginning of August since the 11,280 seen in 2010, when a severe drought in the Amazon shrank the Rio Negro to its lowest level in 109 years. Fire season usually begins in late July and intensifies as August begins.

July also saw an increase in fires: there were 6,803 fires in the Amazon last month, 28% more than in July 2019.

“I’m really worried,” said Ane Alencar, director of science at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM). “We can expect a catastrophic burning season.”

The relative increase in hotspots within Indigenous territories was even higher than the biome as a whole over July, jumping 77% to 540 blazes from 305 in 2019. Conservation areas also saw a higher increase, with fires in state parks 51% higher than July 2019 and federal parks seeing a 48% rise.

Land grabbers don’t work from home, illegal loggers don’t work from home

Fires in Indigenous territories have continued to increase into August, but less steeply, rising 6% compared to last year. But federal conservation areas saw an 81% increase in hotspots over the past ten days, which was in large part thanks to blazes in one park, Floresta Nacional do Jamanxim, almost doubling from the same period last year, from 172 to 328. The forest surrounds Novo Progresso, the city in Pará state which last August held a “Day of Fire” in support of Bolsonaro.

Experts warned increases in protected areas are likely to be linked to land-grabbing, as routine crime prevention has been hobbled by the pandemic and budget cuts.

“Land grabbers don’t work from home, illegal loggers don’t work from home,” said Christian Poirier, program director of Amazon Watch. “They’re out there in the midst of a pandemic still destroying these forests, still invading Indigenous territories with wanton impunity and Indigenous people have less ability to respond.”

One of the Indigenous territories with the most recent fire spots was Munduruku, in Pará state, with 88 fires in just the past ten days – last year the territory saw 117 fire spots in the entire year, already considerably higher than 2018’s 84 fires.

Indigenous territories are being invaded by illegal gold mining groups and illegal timber groups

Munduruku territory stretches over the Tapajós River basin, which is increasingly invaded by gold miners, who slash and burn jungle to bring in heavy machinery or create landing strips.

Ibama, the environmental protection agency, had been working to remove illegal gold miners from Munduruku land – the pandemic has added urgency to reducing contact between miners and Indigenous people, who are particularly vulnerable to respiratory diseases. But on Thursday, Brazil’s defence ministry suspended the operation following a meeting between environment minister Ricardo Salles and illegal miners.

“Indigenous territories are being invaded by illegal gold mining groups and illegal timber groups,” said Marcio Astrini, executive secretary of the Climate Observatory, a coalition of civil society groups. ”And the invaders are being supported by the government.”

Ranching also plays a large part: in the first ten days of August, INPE data shows a surge of fires in state parks, to 1,233 from 923 during the same period last year. A closer look at the data shows that 947, or more than three quarters, of these recent fires are in one conservation area, the Triunfo do Xingu protected area in the north of Pará state.

The park stretches across areas that are under pressure from cattle ranching, and have some of the highest rates of deforestation in the country. Last year, it had 2,647 fires – the most of any state park. In October, Reporter Brasil identified links between illegally deforested land in the park and two major meatpackers, Marfrig and Frigol.

So far this month, fires are focused in two states, Pará and Amazonas. Between them they account for 74% of all the fires in the Amazon.

Culture of impunity

Since assuming power in January 2019, Bolsonaro and Salles have, at times, appeared to have made environmental destruction an unofficial policy goal. They have chipped away at protective norms, sacked veteran experts, and proposed opening up the Amazon to mining and farming interests. Regardless of whether legislation gets passed, the signals are clear, say observers.

On Friday, the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo reported that the Ministry of the Environment (MMA) was reducing the number of helicopters available to Ibama for both crime prevention work and fire-fighting throughout the entire country from six to four.

“Six helicopters were already too few,” said a source within the MMA who was not authorised to talk to the press. “It is very frustrating.”

Beth Uema, director of the National Association of Environmental Employees, said that the MMA is expected to cut next year’s budget for environmental protection agencies by between 20 and 25%, on top of a 25% cut this year.

“The current management not only confirms, but strengthens our worst fears regarding trying to continue our work defending our greatest asset, the environment,” she said. “There is a very strong feeling of demoralisation within the agencies.

Last year saw a rise in fires across the Amazonian region as a whole – but the rise in fires in Indigenous areas was particularly pronounced. There were 30% more fires throughout the Amazon biome than in 2018, but 67% more fires in Indigenous territories. State and federal conservation units saw increases of 68% and 34% respectively. Experts at the time warned that loggers and ranchers, emboldened by Bolsonaro’s election, were taking the opportunity to invade and clear protected land in the Amazon.

Although Bolsonaro has made recent gestures towards preventing the fires following a wave of criticism from international investors, critics say they have been insufficient to offset the feeling of impunity on the ground.

Earlier this year, the Bolsonaro administration attempted to push through a measure dubbed the “land-grabbing law” which would have weakened safeguards against deforestation and the invasion of Indigenous lands.

“In the field people are really confident that the government will legalise these invasions and will legalise gold mining inside the Indigenous lands,” Astrini said.

Why are fires set in the Amazon?

Fires don’t naturally occur in the Amazon; they are set to clear land. Selective loggers often arrive first and remove the most valuable hardwoods to sell. The remaining big trees are pulled down with chains and left to dry out for a month or two during the dry season, which begins in April.

Fires are set to clear the felled wood and remaining vegetation, usually so that it can be planted with pasture and grazed by cattle. Sometimes – especially in drier years and when set by people with little experience of land management – these fires can burn out of control and jump in the surrounding jungle, causing forest fires.

This, explained Alencar, is why soaring deforestation is likely to lead to a worse fire season.

Last month, Embrapa, a research body linked to the Ministry of Agriculture, said that 90% of 2019’s Amazon fires were in areas that were already degraded and used for pasture, rather than linked to new deforestation.

But an analysis released last week by IPAM found that in 2019, 34% of fires in the Amazon were in newly deforested areas – the highest rate in the last four years. A further 30% were forest fires, which occur when a fire intentionally set to clear deforested land escapes into adjacent standing jungle. Only 36% were to manage existing agricultural properties.

“It is not grass fires that create those clouds of smoke that intoxicate the Amazon and travel to the Southeast, it is a tree burning, felled or standing,” Alencar wrote in the study.

Vicious cycles, dryer weather

Last year’s fire season was particularly intense – August alone saw 30,900 fires, the highest number since 2010 – but heavy rains in September and the absence of extreme drought prevented 2019 from breaking records overall.

But the spike in large fires set to clear land was unusual, resembling deforestation patterns from before regulations to limit large-scale burning and clear-cutting were passed in 2004.

“The real nightmare scenario would have been deforestation fires at the level we had in 2019 during a drought year,” Alberto Setzer, a senior scientist at INPE, told Nasa’s Earth Observatory earlier this year. “You would have seen fires spreading into the rainforest and burning unchecked for months.”

Worryingly, this year is forecast to be considerably drier – peak rainy season, which runs from December to February, recorded only 75% of the usual rainfall, and data from Nasa and INPE indicates stressed climate conditions that could lead to a more flammable forest: drier soil, hotter temperatures and reduced groundwater.

The capacity of forest to recover decreases immensely… We are changing the ecosystem

Nasa has also suggested that the unusually warm North Atlantic waters that are driving an intense hurricane season on the eastern coast of the US could intensify the Amazon’s fire season, Alencar said.

“The scenario could be catastrophic, because we have material to be burned, we don’t have the political will to fight criminal activities leading to deforestation, and if we have a climatic event on top of that we would be in a very bad situation,” Alencar said.

A drier climate would increase the chances of deforestation fires escaping into primary forests, especially along forest edges, said Paulo Brando, a tropical forests ecologist from the University of California-Irvine. These forest fires themselves create desiccating and destructive feedback loops that increase the chance of yet more fires.

“If forests lose their big trees, they also lose the humid microclimate that prevents fires from spreading, the sources of fruits and seeds, and important ecosystem services,” Brando wrote in an email.

If it were just one fire, the forest might recover, given 20 or 30 years, said Tasso Azevedo, the coordinator of MapBiomas, which tracks Brazilian land-use change. But when fires happen repeatedly year on year, the forest has no chance to recover.

“The capacity of forest to recover decreases immensely. Probably after three or four times you have a fire, it won’t recover any more, and if it’s not recovering, it’s getting drier, there is less resistance and it is more inflammable,” Azevedo said. “We are changing the ecosystem.”

“We are very close to 20% [of Amazon deforestation], so from now on we are at risk of a point of no return,” said Azevedo.

Agencies in trouble

The increase in fires comes despite a July 15 ban by President Bolsonaro on setting fires in the Amazon for 120 days, and a costly and splashy deployment of the military to take over responsibility for tackling forest crimes.

Setzer, the INPE scientist, said that a similar decree made last August following intense international pressure was effective in the states where the army was present.

“Once you have the political will, and the technically means, using the army, the federal police, the Ministry of the Environment agencies, you can reduce the number of fires significantly,” he said.

But critics say the money spent sending the army would have been better spent on refunding the agencies who have been trained to reduce deforestation and fire-setting for years.

“The deployment of the military is window dressing. It is a smokescreen, designed to appease the valid concerns of global market leaders,” Poirier said. “On one hand [Bolsonaro] talks about fighting deforestation with the Operation Green Brazil and with the other hand they are destructuring and defunding the very institutions who do it for less and do it better and have the experience.”

Sources within the Environment Ministry who spoke on condition of anonymity said the army is unfamiliar with the logistical difficulties of working in the Amazon and do not know how to fight fires. One source added that senior members of the administration had been unwilling to listen to their objections to being subordinated to the military.

“We are living in a moment with the government that there is not much dialogue, they come and send, they don’t ask, they don’t discuss,” they said.

Inspection agencies have been struggling with budget cuts, staff shortages and interference from the Bolsonaro administration.

The Folha de S. Paulo newspaper reported that the number of fines for environmental violations imposed by Ibama in 2019 was the lowest in 24 years.

The Ministry of the Environment did not respond to a request for comment.

Not just the Amazon that’s burning

A drought in the Pantanal, the world’s largest continuous wetland, has caused fire spots there to more than triple so far this year. July’s tally of fires, 1,684, was the highest recorded since INPE’s records began in 1998 and more than four times the average for that month.

The wetlands flood seasonally, exposing vegetation in the dry season. So far this year, to August 10, INPE’s satellite has registered 6,388 fire hotspots, more than treble those during the same period last year. One huge blaze in the wetlands has already consumed 600 sq km of vegetation in less than a month, making it the biggest fire in the region for 14 years.

The fires appear to be accelerating – there were 2,170 fire spots during the first ten days of August, more than 600% higher than during the same ten days last year, Unearthed analysis has found.

Ecologically crucial and enormously biodiverse, the region is home to hundreds of bird species and large mammals like jaguars and giant anteaters.

Vinícius Silgueiro, territorial intelligence coordinator at Instituto Centro de Vida, a forestry NGO based in Mato Grosso, said that the fires in the Pantanal could be partly attributed to the acceleration of Amazon deforestation, which has caused rainy seasons in the region to shrink and droughts to become more severe.

“This deforestation has a severe impact on the phenomenon known as “flying rivers”, in which the humidity of the forest originates a large column of water, which is transported by air to vast regions of South America,” he said.

Silgueiro said data indicated that most fires were set to create or renew pasture, but that drought had helped them to escape and spread.

“The numbers of hot spots show that this year will be as or more critical than last year,” he added.

A version of this story appeared in the Guardian.